By Robert Bradford Lewis

Fortune brings in some boats that are not steer’d.

-William Shakespeare

Introduction

The Phaistos Disk, housed today in room three of the Heraklion Archaeological Museum at Heraklion, Crete, was discovered by Dr. Luigi Pernier on July 3rd 1908, at the ruins of the palace of Phaistos on the island of Crete, which structure collapsed CA 1400 BCE. The disk, made of fine clay and measuring about 15 cm (roughly six inches) in diameter, was blind printed while the clay was wet, it was then fired; possibly sometime in the 20th century BCE. The technology for creating the Phaistos Disk has been cited as an example of movable type. This is simply false. Movable type is, practically speaking, a “brand name” for the printing process invented by Gutenberg, et al. In the Gutenberg system, reverse image cast metal types, or punches, are aligned together within a frame of fixed rows, producing a mirror image of the item to be printed. This arrangement is then inked and paper is placed on top of it.

When it becomes time to print some new matter, the type can be dumped, and new text inserted, or set, into the frame of fixed rows. That’s why movable type is called movable type. This technology requires a press for imprinting a right way round image upon the paper to be printed.

The combined technologies of cast metal type and press, however, were not introduced to the west until the 15th century of the Common Era, both of these having Chinese prototypes from the 1st millennium CE. The technology that preceded it, required the use of carved blocks of wood or stone with the reverse image of the item to be printed engraved upon them, literally carved in stone; unmovable, hence, not movable type. The disk’s signs were simply pressed into the clay by hand with punches, one at a time and not by any mechanical process. Therefore, if we are going to call the Phaistos Disk an example of movable type printing, we might as well call every cuneiform text ever unearthed from the amnemonic sands of the ancient Near East, the end product of movable type, since the technology is the same: a human hand, with a stylus or punch, impressing graphemes into wet clay. If cuneiform — the worlds oldest extant writing system — can be called movable type printing, then as an example of printing by means of movable type, the Phaistos Disk is of no great moment of all. But this is not the case. The Phaistos Disk is full of superlatives, being an example of movable type printing, however, is not among them.

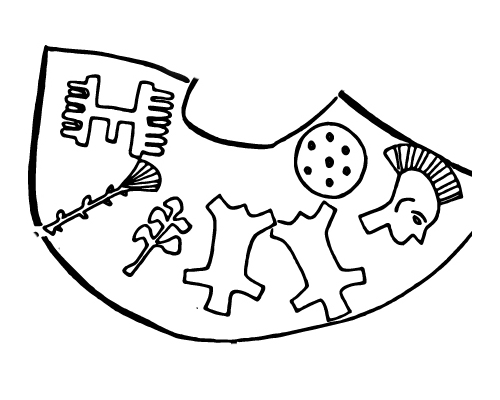

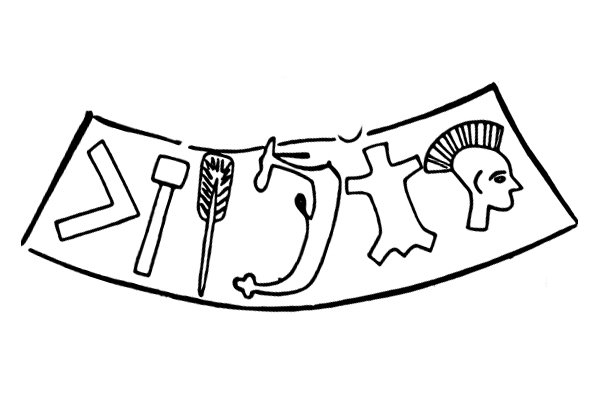

The disk’s signs, seemingly inscrutable images from the everyday life and concepts of its culture, cover the disk in a spiral pattern on both sides, divided into 31 cells on one side and 30 cells on the other and number a total of 46 (counting the oblique slash, which, all things being equal, no evidence requires us to discount as a sign) unique signs. These signs repeat 259 times, 132 times on the recto side and 127 times on the verso side — again, counting the oblique slash, of which there are 17 total on the disk. No one need take my word for any of this, since there are actually very good photos of both sides of the disk on the otherwise somewhat contentious Phaistos Disk Wikipedia page, and you can enlarge any area on the disk with a click. All the signs may be counted effortlessly there (I use Sir Arthur Evans’ numbering at all times here) and please, count the oblique slashes in particular and see; there are nine on the recto side (at A5, A10, A11, A13, A16, A17, A20, A29 and A31) and eight on the verso side (B1, B5, B7, B10, B11, B13, B25 and B28). My advice is that you should always have these disk images at the ready in new tabs, while perusing this decipherment.

Many claims of decipherment have been put forward over the years, but thus far, none of them have earned the approval of the larger scientific community. I have attempted a decipherment of the disk, from first principles. Undoubtedly there will be mistakes (no decipherment springs perfectly formed from the head of Zeus), these have been and will be corrected as I discern them; every conclusion in this undertaking should stem from hard-boiled scientific principles after all, and if I can, I will show you the reader, the rationale behind my conclusions, every step of the way.

The Received Wisdom

There is much said and written about this disk that can be categorized under received wisdom, i.e. perpetuated error. Much of this received wisdom is treated as “established fact” by otherwise smart and talented scientists who, evidently, have never attempted their own decipherments of the Phaistos Disk, and really, too many of those researchers who have attempted their own decipherments, have simply followed blindly along. Unexamined assumptions about directionality, writing system and provenance, are a few examples of this blindness. Directionality seems to me the most egregious of these, since I believe that this inability to see is simply a matter of lax observation. Provenance is the least blameworthy, since the Phaistos Disk was, after all, discovered on Crete. But is the Phaistos Disk from Crete? I submit that it is not. And to assume that the Phaistos Disk is Minoan, simply because it was discovered on Crete, is like assuming that the Gundestrup Cauldron must be Viking, because it was found in a Danish bog; we know better of course. But if the Phaistos Disk is Minoan, then someone should probably explain, why its clay is of non-Cretan type, as Gustave Glotz (1925:381) has observed; why the disk’s edge is so finely formed, which finely formed edge is a cut above the usual Minoan technique; and why the disk was deliberately fired, which firing was not the standard Minoan practice. And perhaps do so without resorting to accusations of forgery, since my research (as you will see) indicates that this disk is the genuine article; in this regard, lime scale deposits observable on both sides of the disk and its interstices, might be relevant. A sufficiently evidenced decipherment that posits a non-Minoan origin for the disk, should answer these particular problems well.

In any case, it occurs to me that over 100 years of “received wisdom” based decipherment attempts, have gotten us nothing that is unarguably convincing. Perhaps it is time to put aside certain of these received wisdoms for a moment and try a different, empirical approach; an approach based as much as possible on raw data, rather than received wisdom. One starts this process with the unrefined evidence presented: the disk itself, and the close investigation of its signs, before moving on to hypothesis. This is the inductive half of the inductive/deductive loop that all science must follow. One then builds a lexicon. Any hypothesis is then tested by the possible teasing out of words and sentences, using the lexicon and based upon what has been hypothesized from observation. This is the deductive half of the inductive/deductive loop. To quote archaeologist Andrew White, “Once you are in this loop, you are doing science”. If the words and sentences detected are intelligible and accord anthropologically and or archaeologically and or mythologically and or religiously and or grammatically and or literarily and or poetically with a fixed historical period and geographical location, then one continues the process. If not, then back to square one and the raw data again, before establishing or rejecting any additional hypotheses. Only then can any theory be established. But first we must remove the jumble of scrap and landfill. Removing from our storehouse of knowledge the clutter of a century’s worth of phonetic attempts and syllabic assumptions alone, however, will nearly empty it, and we will need to refill it piece by piece, from the concrete floor up. Let us proceed.

Directionality

One of the most damaging of these “facts” to serious Phaistos Disk research, is the direction of reading. Truly, I have never read a comprehensive argument for a right/left reading of the Phaistos Disk. The left side crowding that some have used as an argument for this, is as far as I can tell, virtually non-existent. Crowding is almost always on the right, which argues for a left/right reading. A27 demonstrates this quite well, as does A3 and B3.

If we look closely at photographs of A27, we see that the back of the mohawked man’s hair, over stamps the shield to its left, thereby proving a left to right stamping of those signs. This is an instance where the received wisdom must take a backseat to the physical evidence, all objections to the contrary notwithstanding. Studying the disk, we can easily guess that the lines were incised first, and the stamps were laid down after.

In A28 is an example of crowding on the left side of its cell. Investigating this area, one detects correction. The area was made too small, and when the artist ran out of room, they simply rubbed out the line, re-stamped the images and re-drew the line around the stamped images, on the right side.

As for center crowding, any crowding detectable there is either deliberate (B1), or the result of trying to fit seven signs into too little space (A3). As such, B1 is no argument for directionality at all, and A3, if anything, argues for a left/right reading. In fact, there has never been a Greek writing system that read exclusively right to left. Sometimes these ancient systems would read vertically, sometimes boustrophedon, yes, but never exclusively right to left. And although the disk is not Greek in origin, it might be worth pointing out — for those who insist that the Phaistos Disk bears some relationship to Linear B — that Linear B, reads left to right. Evidently, for the most part, so does Linear A.

Where to Begin

The Phaistos Disk reads left to right. Starting from the center of the disk would be the most logical place to begin a left/right reading of the disk. My having deciphered the verso (B) side first, demonstrated clearly to me that the recto (A) side, center, is the correct place to begin.

A Word About the Writing System

I have looked for a syllabary here. I have searched for phonemic orthography and an alphabet here as well. Their likelihood here seems remote, to the best of my ability to discern, and frankly, I have found a perfectly serviceable solution in a writing system comprised entirely of logograms, pictograms, compounds and determinatives. The system then, will be called logographic. As will become apparent, however, the signs found here, are atypical, since they encode neither phonetics nor grammar; the grammar present here is context and word order based, rather than spelling based. Very well, we have a hypothesis regarding the writing system and directionality, and presumably we have a culture to go along with it. Where then is the corpus that would have served a language or for that matter, any culture?

This question of corpus, by the way, is better put to syllabaries belonging to cultures literary enough to have authored the disk, which systems would probably have created texts at a faster clip than any logographic systems could. Certainly any logographic system meant to serve the writing needs of an entire language, and which system employed the punch, would require many more punches to hunt and peck for, than the 46 signs found here. The speed alone at which individual punches could be located in a syllabic as opposed to a logographic system, would ease the process considerably. One needs approximately 41 to 99 signs for a syllabary to serve the writing needs of an entire language. These signs could be carried about in a leather bag tied at the waist; a logographic writing system requiring punches, might conceivably need an entire room just to house it. And we do have 46 signs here, but one does not simply toss a syllabary away after authoring one text, one creates a corpus. So where is it? How do we account for the missing texts that a syllabic writing system would have produced, or for that matter, the missing punches — thousands of them for all we know — that a logographic writing system would have necessitated?

This is not to say the Phaistos Disk was never re-printed, almost certainly it was. But even if we had 25 copies of the disk before us, having still only 46 unique signs to work with, we would find ourselves not much better off.

What are we to do with the raw data of only 46 unique signs and no corpus? Consider: what if the signs in question were not meant to serve the writing needs of the entire language, only the story on the disk. In which case 46 might do. 46 signs, one of which (the flower) is actually a determinative. Another (the walking man), is both logogram and determinative, as we shall see. A lexicon has been provided (see the menu at the top of the page) so that the reader might check my work. And do look by all means, because the legitimacy of this decipherment depends entirely upon the accuracy of the signs as I have defined them, and the narrative that accrues when they are read in the proper order.

The Story

What information can be found on the Phaistos Disk? In the 20th century of the Common Era, there were eight million stories in The Naked City. In the Bronze Age, mostly just four stories, to wit: how the gods came to be, how the world came to be, how the kings came to be and of course, the ubiquitous, mythical, worldwide flood. The Phaistos Disk contains at least two of those stories. On the recto side is a royal genealogy of deified kings, and on the verso side, is a mythical flood narrative. And this flood narrative contains aspects of both a local flood, and a world wide flood. It is a very old story, indeed. A glance at the recto side reveals easily the genealogical aspects of the disk. A10, A13 and A16 contain the signs for “king” and “deified”. At A11 and A17 are the words “he fathered”. Next to these words at A9, A12 and A15 can be found the names of these kings. If my estimation of this document’s age — roughly 4000 years old — is correct, then the Phaistos Disk is, as of this writing, the oldest complete (that is, not assembled out of random fragments of varying age and quality, etc.) flood text that we have.

I use the term decipherment here, loosely, as do all other “decipherests” of the Phaistos Disk. The disk cannot be deciphered, because the disk is not a cipher in the first place. It is not a cipher, because the disk is not made with an alphabet and all ciphers are alphabetical at their core. What we have before us then, is a narrative consisting of a code of sorts. One that had never been seen before and which was — deliberately — never used again. And undoubtedly they had some syllabic or logo-syllabic writing system for everyday writing tasks, so they would not have needed their “Phaistos” script for that. This code differs from all others in one utterly important respect, however: it was not the intent of its authors for it to be hidden. I submit that this text was sent to perhaps a half-dozen city states throughout the eastern Mediterranean and Near East, announcing the arrival of a new power in the world. This is the usual “making a name” that one finds throughout the literature of certain ancient texts.

The Phaistos Disk contains the mythologized history of a family; that is to say, it encompasses both history and myth. It is a story as violent and lusty as any saga. Written at the dawn of Western civilization, it is one of the founding documents of our Western religious systems, having profoundly influenced the Primeval History of Genesis. And this text anticipates — in more than a few respects — both Jung (heroes’ journey) and Freud — Id (Child-One-Side), Ego (He-With-War), Super Ego (Our-High-King) and Oedipus, as one would expect, since myths are exactly where both Jung and Freud got their ideas. This story was a story so altogether holy to its authors, that out of reverence for it, this unique writing system was tailor-made, given to it and then studiously put aside. We are remarkably fortunate to have it.

The Language of the Disk

The Phaistos Disk was written by a people, which people certainly spoke a language. That language was Ugaritic — not to be confused with Ugric, as in Finno-Ugric, a language family entirely unrelated to Ugaritic. Ugaritic is a Northwest Semitic language and very closely related to Hebrew; so much so, that like Hebrew, it is spelled without vowels. For those of you who can neither read nor write in Ugaritic, however, this will be of little help, and I am certainly no expert. But one needn’t be an expert in Ugaritic, in order to know things about Ugaritic; text books can be quite helpful in this regard and the strongly pictorial (and non-alphabetic, non-syllabic) character of this technically logographic writing system, makes this writing system — for our purposes anyway — largely non-language specific (although elements of the language’s grammar do, occasionally, express themselves), therefore giving itself well to translation by the non-Ugaritic reader. The vocabulary too is very basic and limited to ideas as common today as they were then. Therefore, if the disk is deciphered word for word — although due to the limited Ugaritic word-stock, some paraphrasing has been necessary — the original word order will be preserved intact. This understanding is vital to a decipherment of the Phaistos Disk.

It shouldn’t come as any surprise that the Phaistos Disk has its origin in the city state of Ugarit. Ugarit was a multicultural society, and although it was not the cradle of writing (that would be Sumer), it was the nursery school of writing par excellence; no less than eight languages were spoken at the height of its culture. At this cultural apex, in the 15th to 13th centuries BCE, scribes in Ugarit wrote and or read the Sumerian, Assyrian, Babylonian, Hurrian, Cypriote, Aegean and Hittite writing systems; they were fluent in Egyptian Hieroglyphics as well. This multicultural impetus may even have traveled west; Cyrus H. Gordon has posited a developmental connection between Ugaritic culture and Minoan culture. As for alphabets, it’s certainly true that the Ugaritic people had an alphabet. We know this thanks to the work of Charles Virolleaud, et al. In fact Ugarit invented an early alphabet, a cuneiform alphabet (technically an abjad); but not until about the 15th century BCE, centuries after the disk was made. Their Iron Age cousins, the Phoenicians, bequeathed their alphabet to the Greeks, and the Greeks in turn, bequeathed to us the earliest version of the phonetic alphabet you’re reading now. This marks Ugarit, not as the least likely candidate to have authored the disk, but indeed, a rather likely candidate.

The Rules

There are two different types of sign here, signs of meaning and signs of function. All but one of the signs we will discuss here (the flower sign) have meaning, but a few of those signs of meaning serve specific functions as well, which functions comprise certain parts of speech. As above, there are 46 unique signs on the disk, fully 28 of which mean one thing, respectively and one thing only, whenever one encounters them. Those 28 words comprise the following: attend, barleycorn, beast, branch, child, clothing, death, deified, destroyer, eater, escaped, flood, house, important, number, oar, one, our, place, reed, sea, sired, taken, three, tooth, two, very and woman. 12 additional signs exist within a category of meaning, which categories will include tense, plurals or different parts of speech, depending on the sign. These categories comprise the following 27 words: animal/animals, king/royal, kind/type/types, like/related, boarded/loaded, man/men/maker, our/us, high/over, ox/oxen, ship/ships/boat, side/sided and strike/struck. As with Ugaritic cuneiform, context will sometimes determine the nature of the word in question.

Among the signs of meaning here, there are a few exceptions to the rule of fidelity to meaning. For instance, the oxhide sign for “hides”, “leather” and “oxhide”, can also mean “great” and “greatly”. In Ugaritic, the word for “hides”, “leather” and “oxhide” is msg; the Ugaritic word for “great” and “greatly”, is rb.

There is an oblique slash at the beginning of certain phrases or sentences, which acts as the pronouns “he”, “it”, “they” and the presentative particle “behold”. I find it rather interesting that the presentative particle “behold” (hn), involved in a parasonance with the pronouns “he” (hw), “it” (hw) and “they” (hm) as it is, is used exclusively to introduce men, inanimate objects and groups.

I first learned about parasonance after the fact of deciphering and translating this text. I had decided to spend a day studying the rhetorical expressions of antiquity, when I encountered an online version of G. Khans Encyclopedia of Hebrew Language and Linguistics Vol. 3, P-Z. This was my first knowledge of parasonance and other paronomasia. I then checked the disk for the possible occurrence of these parasonances, etc. The discovery of them here on the Phaistos Disk, took me completely by surprise. Classical parasonance of later 15th century BCE Ugaritic and even later Hebrew type, is a form of wordplay where the noun or verb roots of two or more words differ from each other in only one of their three (or more) radicals. Some of the words in parasonance here, however, are rather primitive, involving only two (as the above example illustrates) and sometimes even one radical apiece. Others here are of a more familiar, classical type. The only cultures in the world that ever produced the parasonance, are the Ugaritic and the Hebrew cultures. The authors of this text were not Hebrews. Since this text constitutes the earliest Ugaritic writing, these puns, perforce, are the earliest examples of parasonance in the world. Remarkable. This business of a sign having more than one meaning, however, is not remarkable, since many of the writing systems of antiquity (e.g. Hittite hieroglyphs and all the cuneiform scripts including Sumerian) contained signs that had multiple values. Even today, with our alphabetic writing systems and spelling based grammars, we have words that are spelled the same, but are pronounced differently and have different meanings, such as bow, the front end of a ship and bow, a knot tied with two loops and two loose ends. We call those words heteronyms.

Two of the disk’s signs categorize signs that not only have meaning, but also serve an important function; one of these, the breast sign, represents the words “came”, “destroyed”, “fell” and “went”, which function is clearly the verb. The Ugaritic verbs for “came”, “destroyed”, “fell” and “went” in the case of this text, are mgy, tkl, qwl and hlk. Three of these verbs, tkl, qwl and hlk, are involved in a parasonance with each other (because there was no alphabet when the disk was fired, the parasonance between qwl and tkl/hlk is strictly aural in nature, since both “q” and “k” are pronounced identically, as a hard k); this is relevant, because most Ugaritic verbs are not in parasonance with each other. But one of these verbs, mgy, is in parasonance with Ugaritic words outside its part of speech, for this breast sign for the verb mgy, is involved in a parasonance with the oxhide sign for the nouns/proper noun, “hides”, “leather” and “oxhide” (see above), msg.

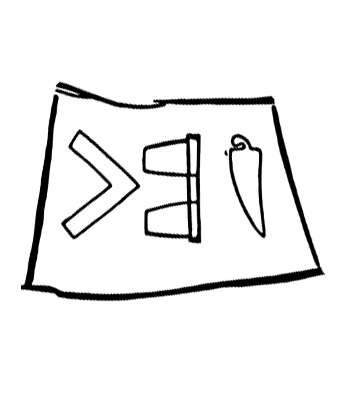

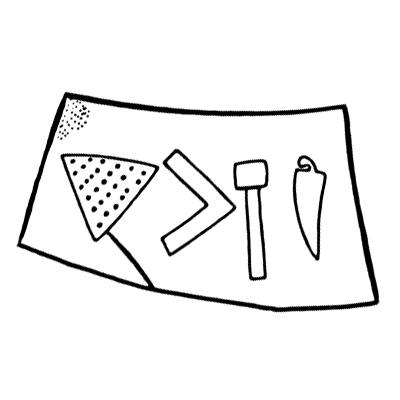

The sideways chevron also serves a function as the words, “for”, “from”, “upon” and “with”, which function is entirely prepositional. As above, these are heteronyms. Significantly, this sideways chevron also houses several puns in one sign, because here, the Ugaritic word “from”, is bd; and it is engaged in a pun with the Ugaritic preposition b,“with”. The Ugaritic words, “for” (l), and “upon” (`al), are also engaged in a pun with each other. And like the breast sign, this sideways chevron sign also puns with one word outside its part of speech, because bd is involved in a parasonance with the oxhide sign for rb, the Ugaritic adjective for “great” and “greatly” (see above). The puns and parasonances of these nouns, pronouns, adjectives, verbs and prepositions, seem deliberate to me. Whatever the case, there are parasonances to be found throughout this narrative that are absolutely deliberate on the part of the authors of this text.

There are also two determinatives, the flower and the walking man. The flower alters the meaning of signs, as such, it is purely a sign of function; and the flower serves the same function every time one finds it on the disk. The flower’s sole function is to turn verbs into adverbs and nouns into adjectives.

The walking man is primarily a sign of function, but it is also a sign of meaning and serves two specific needs, being a determinative and a logogram. As a determinative it turns verbs into other verbs and nouns into other nouns. As a logogram it means “walking”. This phenomenon of a multi purpose sign, is not unheard of in ancient scripts (e.g. Egyptian hieroglyphs, Hittite hieroglyphs, Sumerian cuneiform), so should not come as any great wonderment. We call this phenomenon polyvalence. Admittedly, however, these two determinatives are exotic, one might even say unique, since there are no other determinatives of record that I know of, that deal with parts of speech.

Building Words

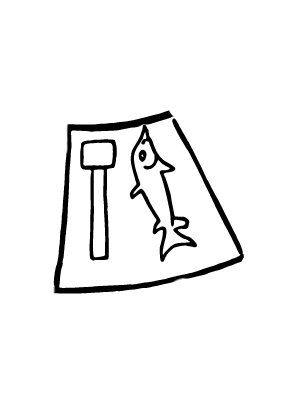

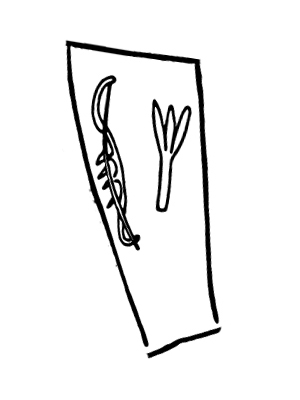

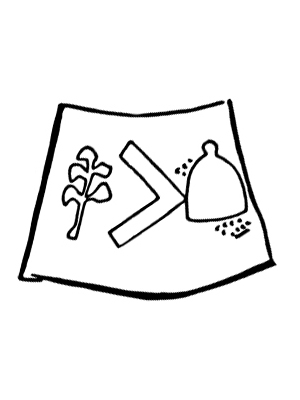

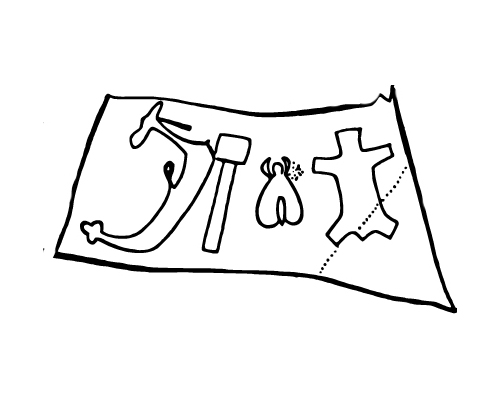

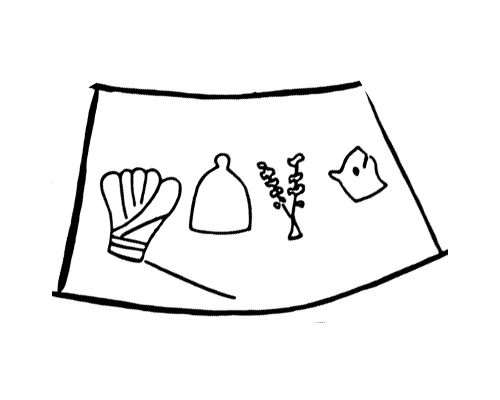

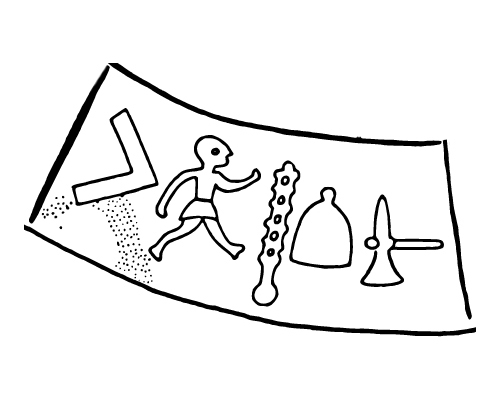

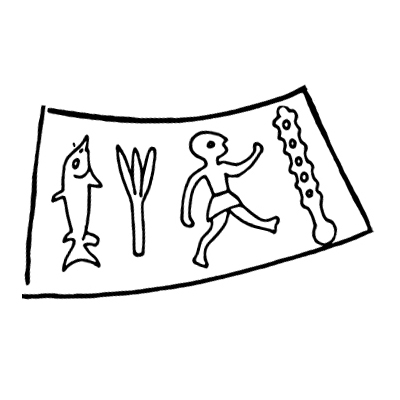

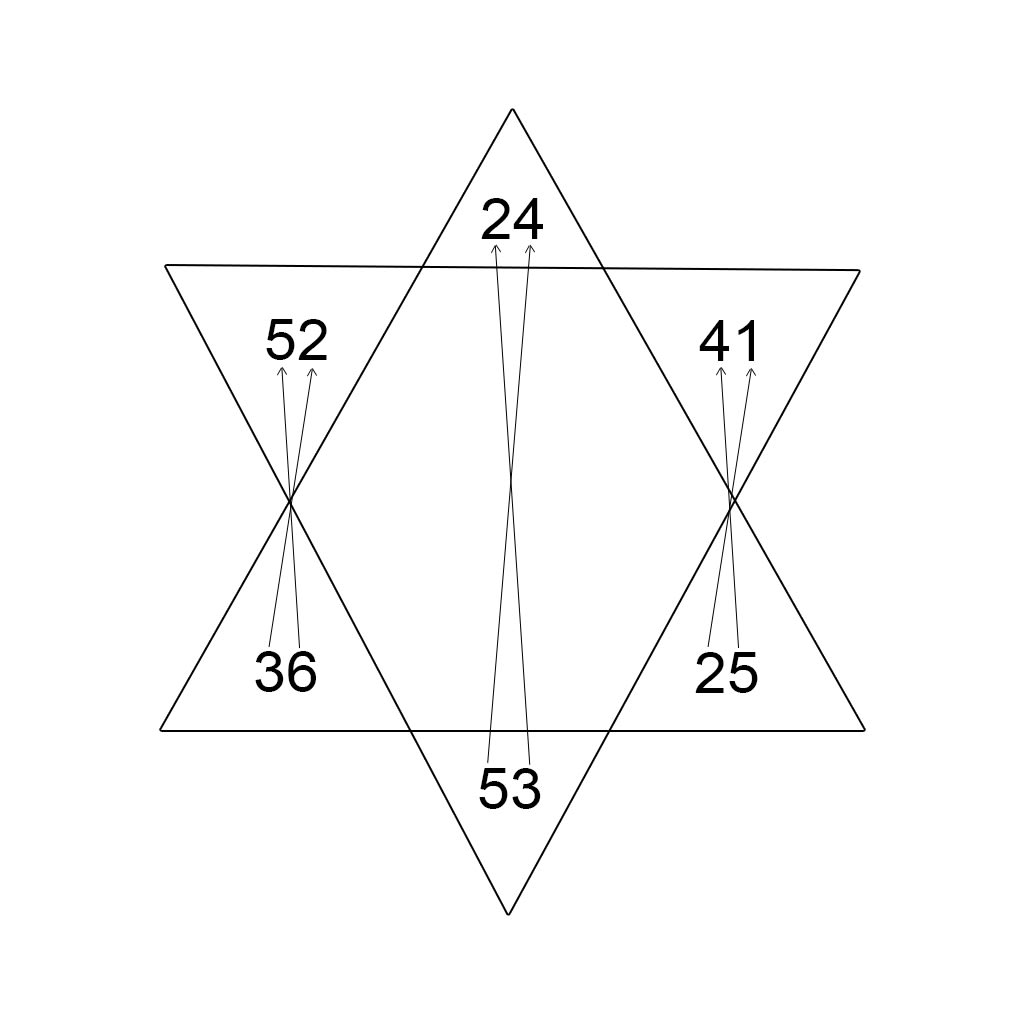

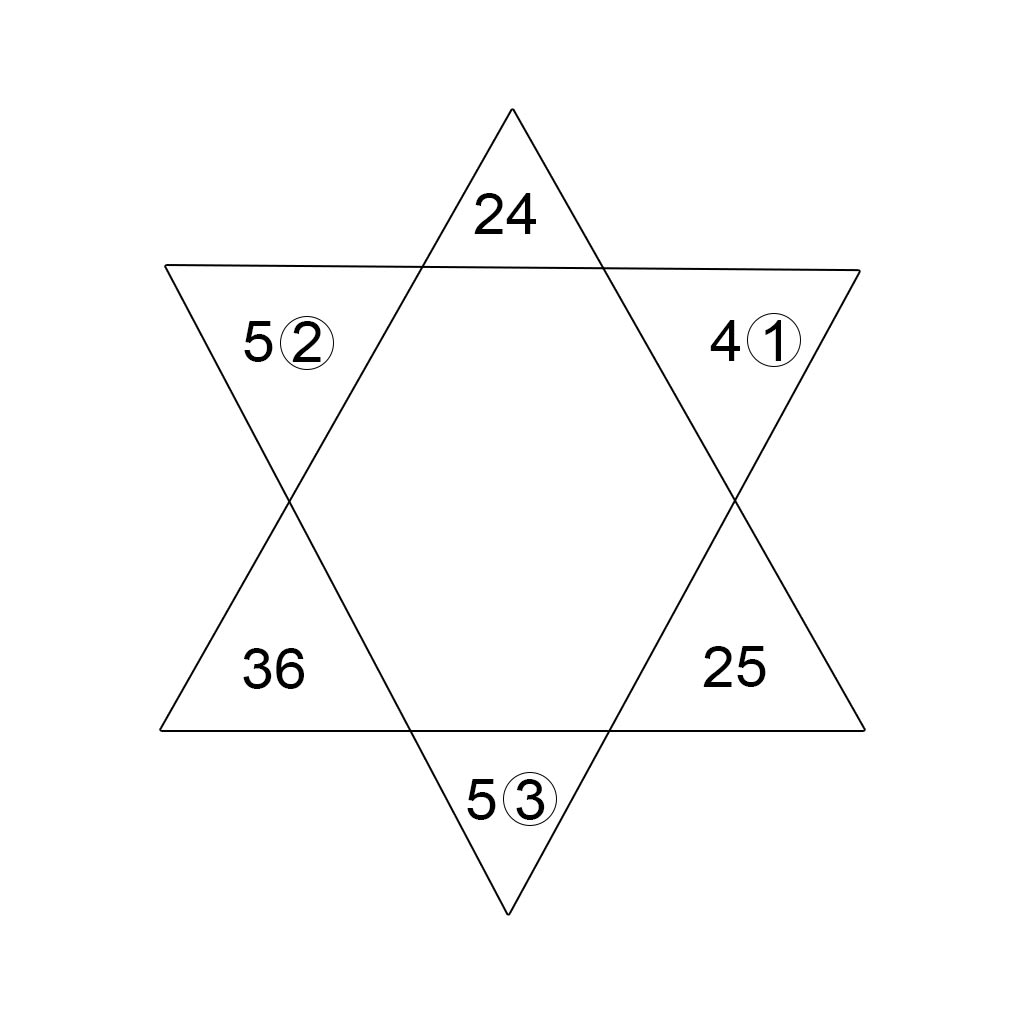

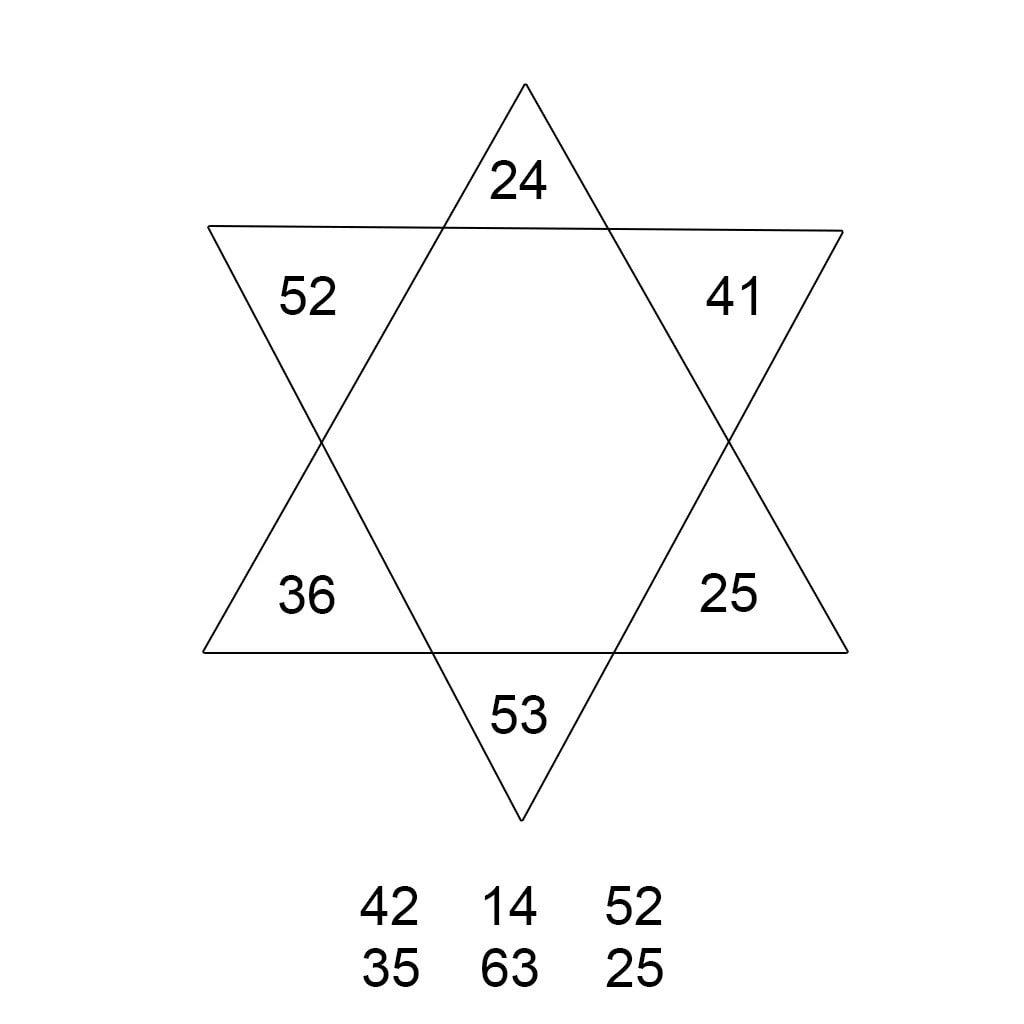

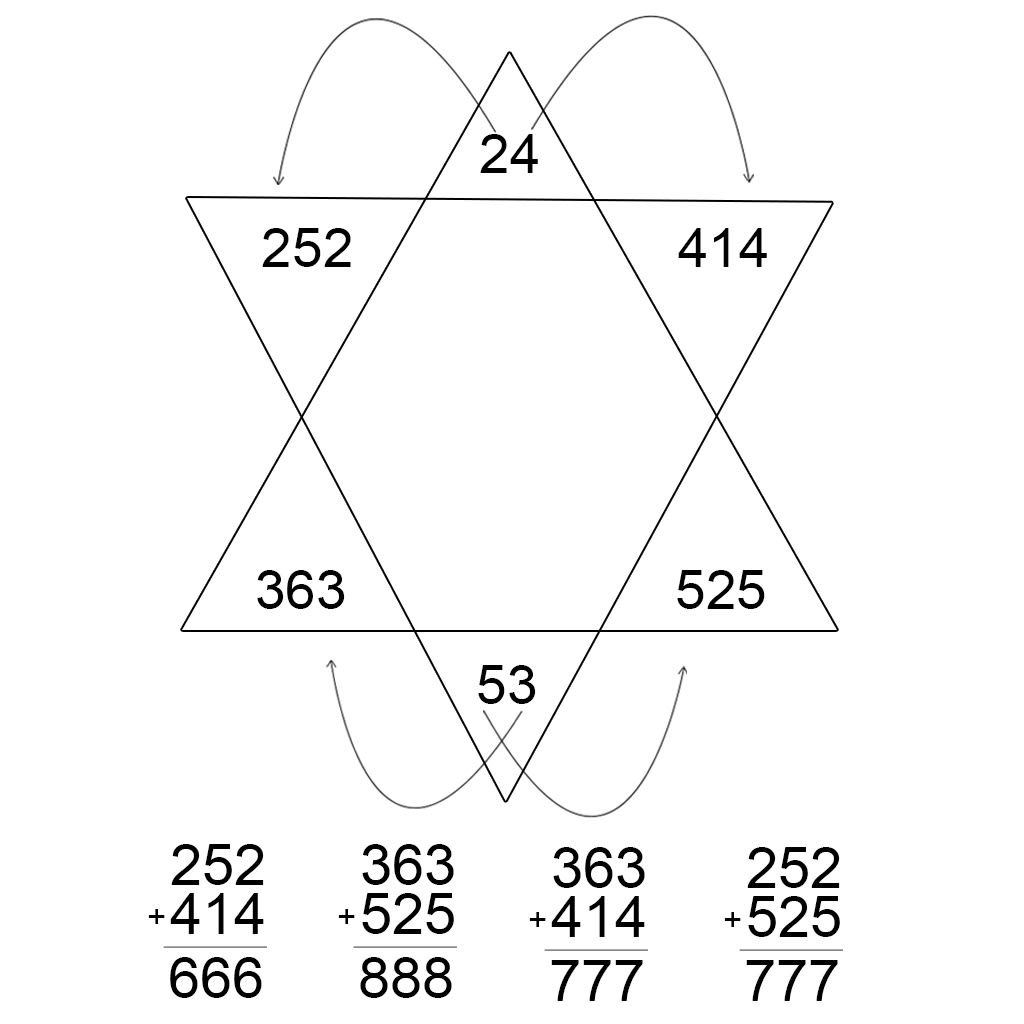

Signs can sometimes pair with other signs to create compounds. For example, the logogram for “like” and “related” is a fish; paired with the walking man, it means “swam” (“walking like” i.e. “swam”); paired with the cat’s head it means “fish” (“like animal” i.e. “fish”); paired with the barleycorn, it means “food” (“like barley corn” i.e. “food”). To the right, is to be found an example of such word usage.

In fact, this text is replete with words made up of multiple signs, either as individual words that have a determinative associated with them, or words made up of exocentric and endocentric compounds; some of which compound words will have determinatives associated with them as well.

The categorical parts of these sign groupings that have determinatives associated with them will not appear in the finalized text of this ancient narrative, nor will the component parts of the exocentric and endocentric compounds, since all of these will have become subsumed within a finalized narrative devoid of loose ends.

The People of the Disk

Archaeologists generally consider the Middle Bronze Age city state of Ugarit (NW coast of Syria, at Ras Shamra, roughly 1000 kilometers or 600 miles east of Phaistos) to have been an essentially Amorite city, since the polity of Ugarit was typically Amorite, as was the case in many other Levantine city states ca. 2000 — 1600 BCE, aka the Amorite period. In this vein, I am of the opinion that it was a Middle Bronze Age dynasty of newly arrived Amorites, who resettled the already ancient site surrounding an abandoned tel at Ugarit (the first literary references to it are in 19th century BCE Eblaic texts), that commissioned the Phaistos Disk. That this disk was produced at Ugarit will, I hope, be demonstrated by, among other things, the sentence to be found at A25 and A26: “sea beast great caused flood great”. The people of Ugarit harbored an ancient dread of just such a mythical creature. The people of Ugarit were also virtually alone among Semitic people in reading and writing primarily left to right, once they adopted cuneiform. The word order (Ugaritic: there are ten V-S-O, two S-O-V and thirteen S-V-O sentences here, for a total of 25 sentences), word play (parasonance and other paronomasia) and style of poetry (involving parallelisms of a markedly Ugaritic feather, including nine chiasms, four formal parallelisms, two envelope parallelisms, one forked parallelism and parallelisms of bicolon, tetracolon, pentacolon, hexacolon and heptacolon type, as well as many number parallelisms) inherent in the disk, also lend themselves to this conclusion. In fact, there are 16 linguistic parallelisms and 63 number parallelisms, in total, within this text. There are doublets here as well, 11 of them to be precise, three of which are flood doublets. This resettlement by Amorites of the previously abandoned site of Ugarit, took place at about the same time, or just prior to, the overthrow of the Neo-Sumerian Ur III city state of Babylon, by other Amorites. The late 3rd millennium abandonment of Ugarit, was probably the result of a drought plagued Mediterranean and Near East. As we shall see, there were others lurking nearby, who coveted this particular location as well.

The “Proof”

It is widely supposed that science has no concept of proof. Nevertheless, science acts as if it knows something akin to it. For example, has science settled the matter of whether the Earth is round (ish) or not? We seem to think it has. In fact, we wager the lives of astronauts, commercial jet passengers, entire crews, and ordinary citizens everywhere — all of these, confident in the idea that satellites orbiting the planet, will continue to assure the safety and convenience of all concerned — on the theory that the Earth is, in fact, round. And when rockets and jets and satellites do crash, we still insist, rightly, that the Earth is round. However this may be, science does suppose itself to have a concept of disproof; which, it seems to me, is merely the corollary of proof, i.e. proving that a given phenomenon or proposition is false. Despite this logic puzzle, it is clear that falsifiability is an integral facet of science (more on this under the heading Falsifiability, bellow); in the meantime, for the reader who can accept the idea of anything like scientific proof for a Phaistos Disk decipherment/translation, this paper offers the closest thing to it, thus far.

The lexicon, narrative and Ugaritic word order in this scientific endeavor, play their respective parts in what I consider links in the chain of proof for this decipherment. A hypothesised lexicon and rules of grammar, wherein all the signs must and do function as the lexicon etc. say they will in every instance, is key. Regarding these fascinating signs and their respective meanings, it might do well to ask how I know that they mean what I say they do. The danger, in this respect, is that I might be accused of engaging in “guesswork”. Trial and error is, I think, the accurate term for it and furthermore, a valid unit of science: “It’s therefore not unscientific to take a guess, although many people who are not in science think it is” — Richard Feynman. And my guesswork is always tested. This process of testing and selection involves, but is certainly not limited to, a conscientious study of the image value of the sign, the context of the sign within the sentence and the context of the sentence within the narrative, in order to identify the idea behind the sign; thus engendering semantic coherence. This hermeneutic approach to the deciphering of the disk, is used over and over again in my analysis of it. Over two centuries of study in these matters validate as well, that genealogies, and the pattern of signs that they demonstrate — very typical of royal inscriptions like the Phaistos Disk — can be most helpful with problems of decipherment indeed. Logic and intuition definitely apply here; these methods are tried and true and cannot be equaled by mere statistics.

A consequence of the lexicon etc. is the narrative that emerges from it, which narrative is not only clear, but which also exhibits decidedly Semitic qualities in cut (parallelisms), plot device (genealogy, flood, flood dragon) and in its use of typical Ugaritic word play, etc.

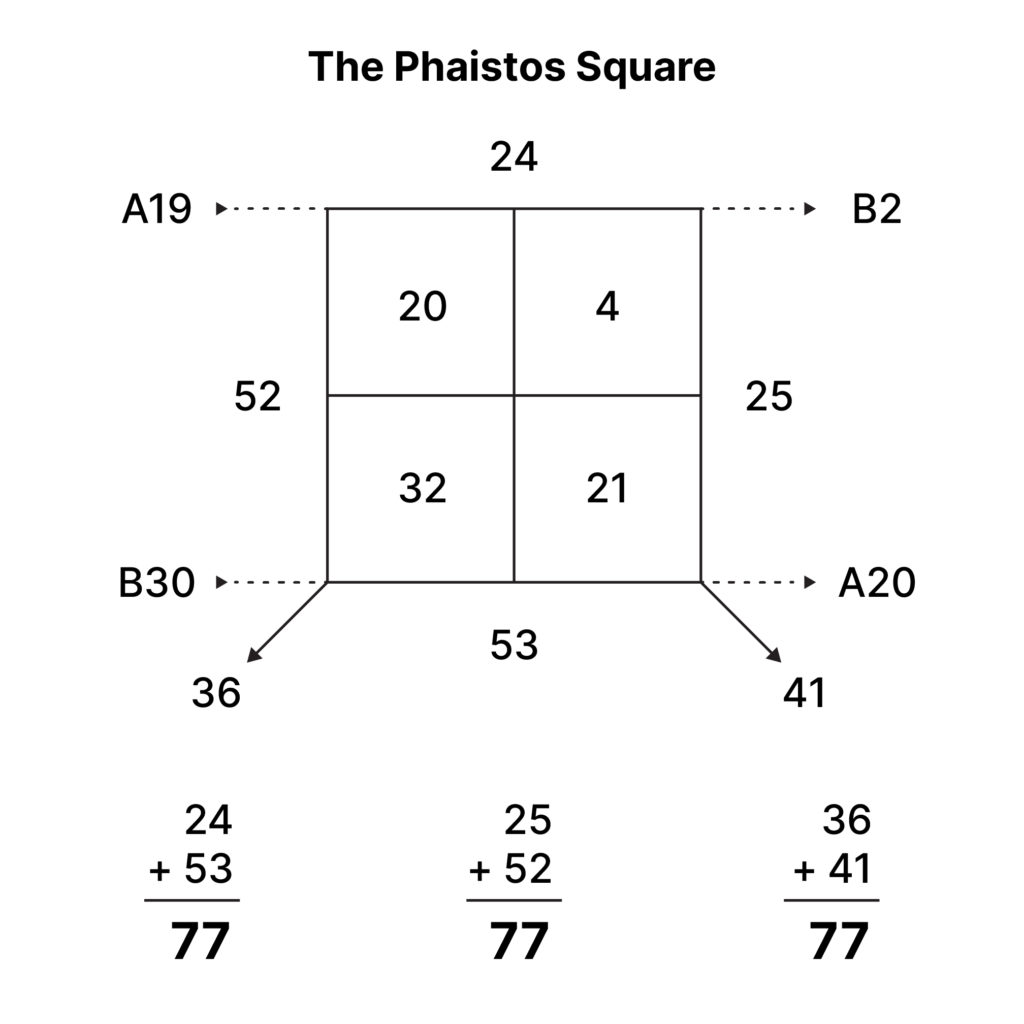

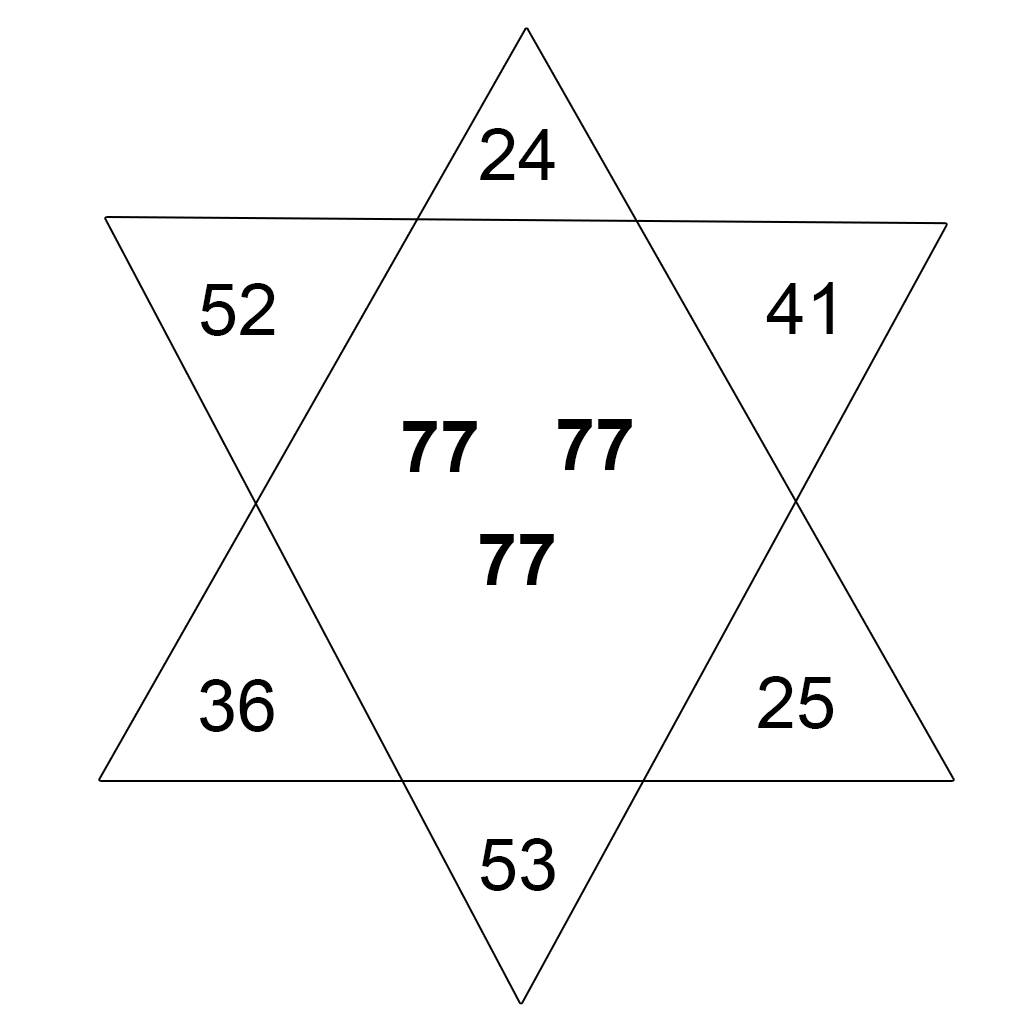

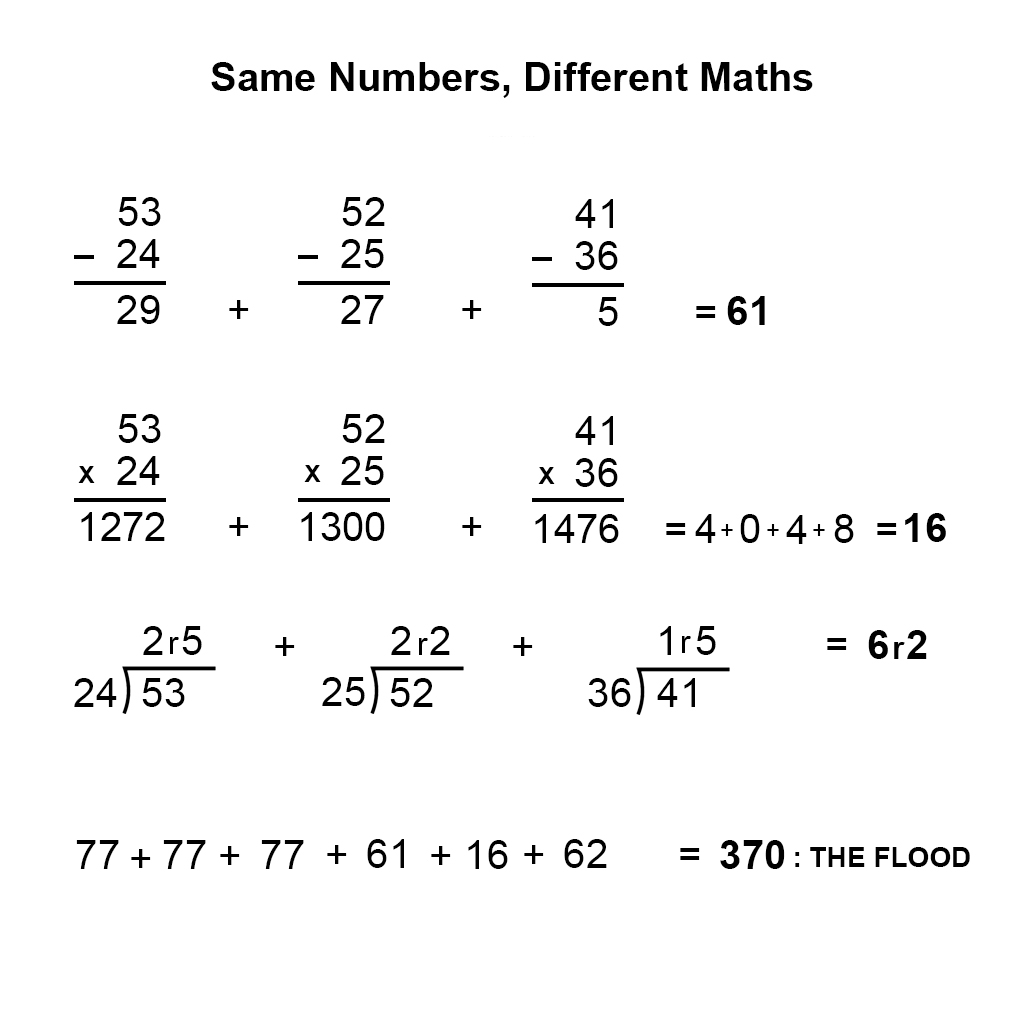

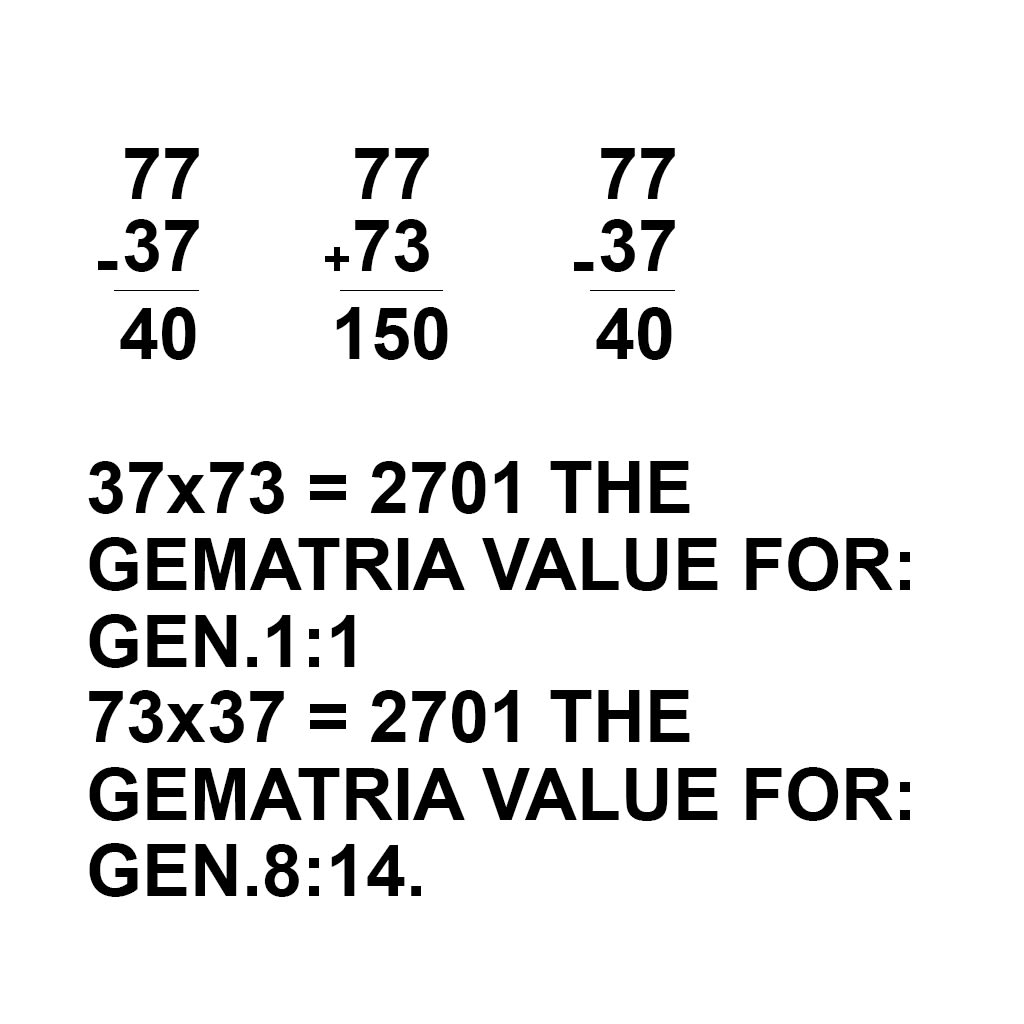

Another consequence of these hypotheses is the mathematics that emerges from the cell count, which elementary school math is watertight. This math can all be investigated by anyone, under the heading; A Few Thoughts on Numbers Mysticism, Exhibits J, K, L and M.

Another important consequence, is the above mentioned Ugaritic word order, which order cannot happen randomly, but must and will show itself, like a fingerprint, if its author is Ugaritic. The dominant word order for Ugaritic is verb-subject-object, subject-object-verb, noun-adjective and possessed-possessor. Subject-verb-object as an alternative (or marked) word order will occasionally crop up in Ugaritic and sometimes the adjective will precede the noun.

I first investigated the word order of the my decipherment to determine if the Phaistos Disk was a hoax or not. I had already ascertained that the artifact I was evaluating was composed of a narrative, and the very idea that a hoaxer would deliberately encode any hoax with an actual narrative seemed absurd to me. But certain voices had been raised in protest against the authenticity of the disk, so in the name of scientific rigor, I decided to breakdown its word order. I reasoned that a hoaxer was not likely forward thinking enough, to have left their native word order, out of any hoaxed artifact written in an undeciphered language, such as Minoan. Therefore if the word order of my decipherment had been Italian or something close to it, it would seem fair to have assumed that Dr. Pernier, of Italian extraction, was the perpetrator of said hoax. I was surprised (and relieved for Dr. Pernier’s reputation, although I had always esteemed him an honest man) to discover that the word order of this text, is Ugaritic; indeed, V-S-O word order in Italian is simply ungrammatical. To quote S.T. Grimshaw, “Not even context may force a V-S-O word order in Italian”.

In all the world, there were perhaps little more than two dozen languages whose writing systems had come into existence during, or prior to, the 15th century BCE, when the palace of Phaistos collapsed on top of the disk. Putting our Bronze Age disk and its curious signs aside for a moment, those writing systems included the following: Sumerian cuneiform, Egyptian hieroglyphics, Eblaite cuneiform, Akkadian cuneiform, Elamite cuneiform, Babylonian cuneiform, Assyrian cuneiform, proto-Canaanite, proto-Sinaitic, the (conjectural) Harappan writing of the Indus valley, Byblian hieroglyphics, Hittite cuneiform, Luvian hieroglyphics, Hurrian cuneiform, Cretan linear A and Cretan hieroglyphics, Mycenaean linear B, Ugaritic alphabetic cuneiform, various other alphabets and Chinese characters. Some of these cultures’ writing systems predate the disk, and those cultures, therefore, are not likely to have produced the disk. That said, how many of the above listed archaic writing systems, demonstrate a left/right reading orientation and V-S-O, S-O-V word order? We can eliminate undeciphered — or at best, badly understood — writing systems like Cretan hieroglyphics, Indus writing and Byblos as entirely unhelpful to our search. Chinese word order is S-V-O and S-O-V; proto-Canaanite and proto-Sinaitic were restricted to meager inscriptions on rock faces and so can give us no secure word order at all. Mycenaean was restricted to lists and inventories and so is also not entirely helpful to our task. Of the remainder, only one, Ugaritic, gives us the V-S-O, S-O-V word order and the left/right reading direction we seek. All the rest that have any corpus we can investigate, have non V-S-O, S-O-V word orders except Egyptian hieroglyphics and, stretching our historical parameters a bit, Phoenician. But Phoenician reads right/left and Egyptian hieroglyphs, which can read in either direction, look nothing like the figures on the disk and anciently, never did.

Now I had a proper word order, but wasn’t I still left with the problem of the ardently wished for external evidence: another text, or whathaveyou, in Phaistos script, the seemingly impossible to find and supposedly utterly necessary solution to the problem of proving any Phaistos Disk decipherment, that a “missing” Phaistos text might certainly (but not in all cases) have resolved? This problem of reproducibility is dealt with here by demonstrating that another such text is not the only type of reproducibility possible, the archaeological and anthropological evidentiary value of clay, sign and cell, is significant; and by showing that our disk had an influence on other ancient texts. As for internal evidence, there are acres of lexical and grammatical cohesion here, so the problem of repeatability is solved. But exactly how many words does another text written in Phaistos script, need to possess in common with our disk, or for that matter, precisely how long does the text itself need to be, in order for it to be an effective tool for testing any decipherment of the disk? No one knows the answers to these questions; and until they do, no one has the scientific authority to say that the Phaistos Disk hasn’t enough data to be firmly deciphered. The blind acceptance of such an idea would constitute an appeal to authority fallacy. This sort of loose thinking is already rampant in Phaistos Disk research. But from the start I knew, that provided both sides of the disk shared enough words in common, and provided that the text were sufficiently long, one could conceivably use the undeciphered half of any partial decipherment of the disk, to test the validity of the principles derived from unlocking the deciphered half of the disk. So that is exactly what I did. And here I’ve found both reproducibility and repeatability: true metrics of precision. I further that these external and internal evidences obviate the alleged requirement for another document written in Phaistos. I say alleged, because in truth this other text, should it ever be found, would be useless to anyone proposing a Minoan decipherment. This is the case, because a Minoan decipherment would still only consist of a lot of sound values, the actual values of which, we still wouldn’t understand, since we still don’t know Minoan. And really, all of this rigamarole would be unnecessary for a decipherment in a known language, such as Ugaritic. We already know that Linear A is Minoan, therefore, if Minoan is ever to be deciphered, this will doubtless come by way of Linear A, not the Phaistos Disk.

The Ugaritic word order, the Ugaritic parallelisms, the parasonances, the paronomasia, the typically Semitic plot devices and the decisive mathematical cell count, are all consequences in this risky, multi-headed hypothesis of lexicon, provenance, directionality and writing system. Taking these consequences into consideration, along with the proportionate number of words shared within this sufficiently long text, and taking into account the Phaistos Disk’s influence upon other ancient texts, the problem of verification is now resolved. This verification comes at the mandate of the evidence, and does not have to depend for its resolution, on a different text written in Phaistos signs. But is this evidence scientific? In other words, is it falsifiable?

Falsifiability

It will occasionally happen, that a scientist is accused of producing a work that is neither provable nor disprovable, that is to say, which does not give itself well to falsifiability. Therefore, in order to counter this charge in advance, I offer the following:

So how should anyone who wishes to experiment, attempt a falsification of this hypothesis? I would begin by attacking the links in the chain of proof for it. First, demonstrate that there are no deliberate parallelisms in its text. Then, demonstrate that my triliteral parasonances aren’t exactly what I say they are. Finally, demonstrate that my word order isn’t truly Ugaritic in character. If you can demonstrate that 51% or more of these phenomena are false, then you will have succeeded. In lieu of this, however, I respectfully submit, my hypothesis stands as proved; since none of these three phenomena, manifestly arising together time and again within the same text, could have happened accidentally. And then there is the math (as above, under the heading: A Few Thoughts on Numbers Mysticism, Exhibits J, K, L and M). If you, the reader, disagree with my paper and any of its conclusions, however, you should feel free by all means to write a review delineating your concerns with it; since any scientist worth the name, looks forward to peer review.

Reading the Disk

Side A, Part 1

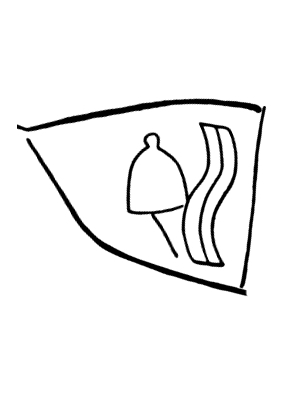

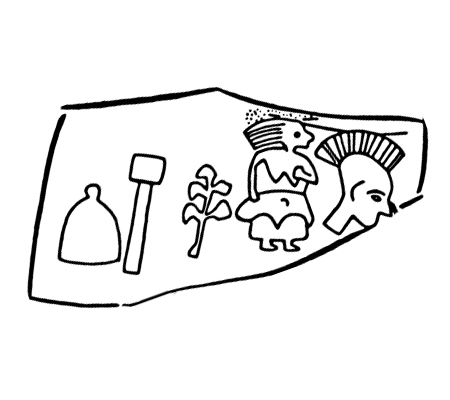

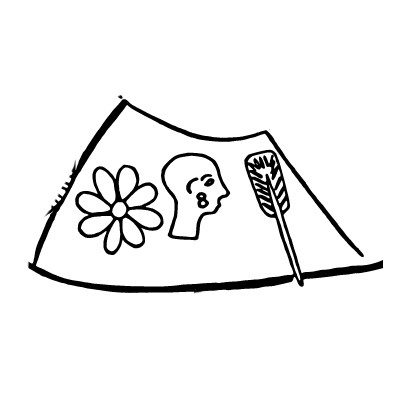

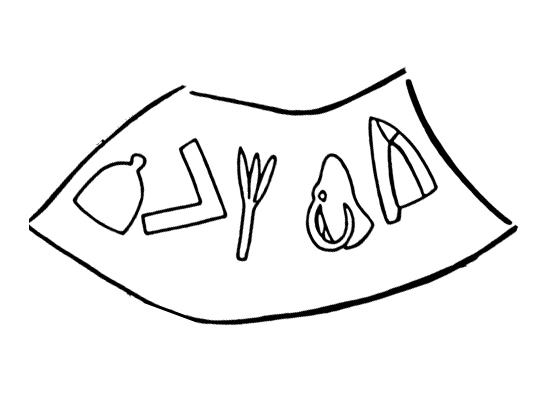

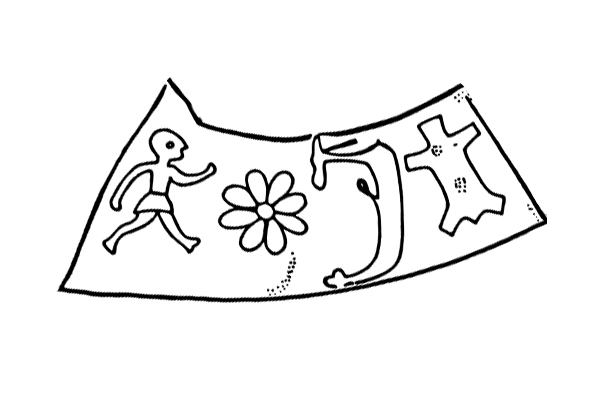

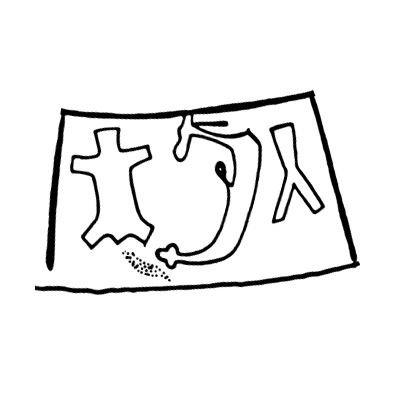

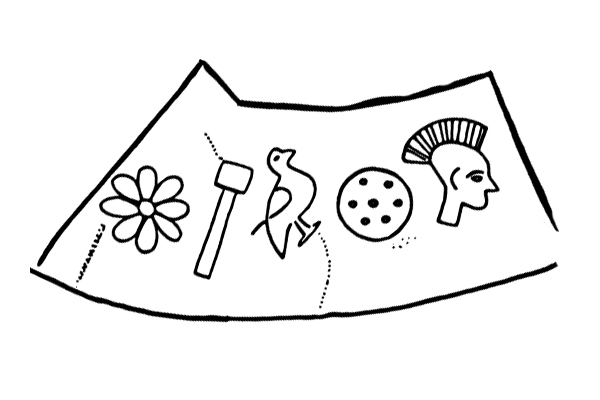

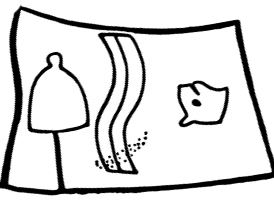

Let us begin at A1, where we encounter our first sign, the flower sign. This sign consists of a flower with eight petals, arrayed around a central disk. This is called a rosette and it became a symbol of ‘Astarte, Ugaritic goddess of love/fertility/sex, the heavens, etc., after her fusion with the Babylonian goddess Ishtar; Ishtar, in her turn, had already become fused with the Sumerian goddess Inanna. ‘Astarte was styled: “Lady-Of-The-Steppes” by early nomadic Amorite worshipers. This sign is a determinative. This rosette is a stylized star, which was Ishtar’s symbol, and it alludes to ‘Astarte (meaning “star”) via a form of wordplay called translexical punning, or allusive paronomasia. This happens when a word or phrase, etc. (in this case, “‘Astarte”), is educed from the reading or hearing of a text, and which words are pertinent to it, but which do not actually appear in the text at hand. Next to it, we see the bald man’s head, a logogram. The man is a slave as evidenced by his face brand, so the meaning of it alone without the oar sign or the determinative, is “attend”, a verb. The bald man is looking rather intently at the oar, which is a pictogram; this gives us the exocentric compound, “attend oar” i.e. “row”, a verb. With the determinative the word becomes the exocentric compound, “manifestly”, an adverb. At A2, the walking man as determinative begins the set. Here, it is determining the sign to its right, the war club sign for the verbs “strike and struck”; in this case, the verb is “strike”. This gives us the intransitive verb “warring”.

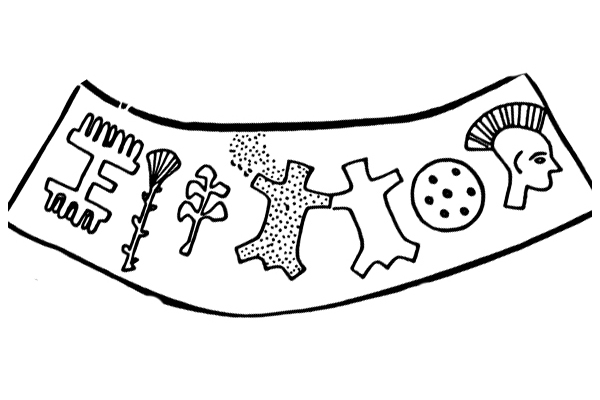

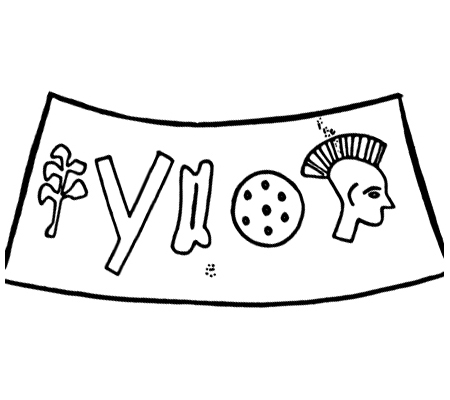

At A3 is found an epithet: “Our-Side-Branch-Great-Great” and please notice the noun-adjective sequence of “side branch great great” that we want in a proper Ugaritic word order. The sign at the beginning of this name looks like an uppercase “E” with fringes. This is a clan type or emblem for another person we will encounter. Her epithet: “Kitchen-Wife”. This sign has been identified by some as depicting a comb; this seems correct to me and it should be noted that since antiquity, the comb has been exclusively associated with women. Whatever the case, it is a logogram and functions as the word “our”.

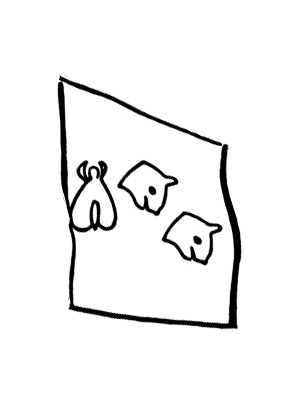

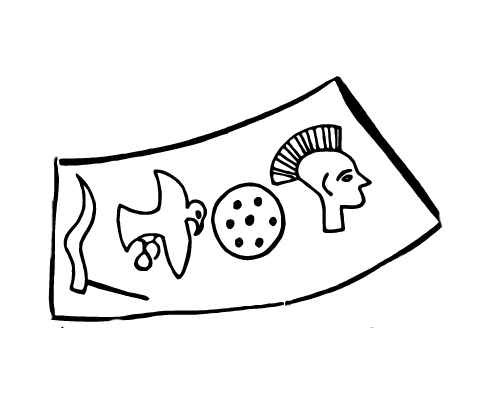

Much has been made of this comb image by Phaistos Disk researchers, due to its similarity to two other Minoan artifacts. Because of these other curious impressions, it is supposed by some that the Minoan provenance of the Phaistos Disk is all but proved. First, there is the sealing impression, on display at Heraklion, which resembles very much our comb. Then there is also a bowl (cataloged F4718), with what has been called a potters mark impressed upon its underside, and this also resembles the comb sign on the disk. Both these artifacts are from Phaistos. What we need to consider is the fact that, in the first place, these images on the disk, on the bowl and the sealing are not identical. The comb on the bowl has six teeth projecting from either side of it. The sealing’s comb has five teeth projecting from both its sides and the sign on the disk has only four teeth on each side. In the second place, these three images appear to have different functions. The disk sign is clearly a grapheme that functions within a writing system. The images on the bowl and the seal appear to be simple identifiers of a product, a workshop, a potter or perhaps the owner’s name. These stamped images having been discovered solely at Phaistos (and having no relationship to any other site), it might even be the case that they were cribbed from the disk sometime after its arrival there. As above, I have given this sign on the disk the value “our” and what better logo could a 15th century BCE pottery workshop want? Other impressions in clay, unearthed on Crete, have been put forward as being identical to some of the stamped images on the disk; these “observations” are all based upon the most flagrant wishful thinking, as none of them resemble strongly the impressions on our disk. The presence of flower and spiral images found on Crete are of no help either, since images of this type are not unique to Crete, but are nigh on universal. Likewise, most of the so called resemblances between the signs on the disk and the figures on the Arkalochori ax, are ambitious at best. Anyway, Glotz said that the disk’s clay does not come from Crete. The clay the disk is made from is the best evidence we have of the disk’s origin — non-Cretan apparently — and until someone proves Glotz wrong, we can safely ignore any evidence these other images allegedly provide, regarding the origin of the Phaistos Disk. Therefore, contra Alice Kober, and with all due respect, the disk should be viewed as non-Cretan until proven otherwise.

The second sign from the left in A3, probably depicts some species of reed. It is also a logogram, and it means “side” and “sided”; here, it wants to say “side”. The next sign in this set is the branch, it is a pictogram and simply means “branch”. This branch sign has five leaves upon it; its leaves are spade shaped and have several lobes upon them. This branch resembles very much a Tabor oak branch. The Tabor oak was one of many trees that were used in the ancient Near East, to depict the `Asherah tree. To the right of this branch are two oxhide signs; each of these, in this instance, mean “great”.

At A4, is the exocentric compound “manifestly” again. At A5, the clause “behold branch number one”. Once again, the diagonal slash at the beginning of any phrase or clause means “he”, “it”, “they” or “behold” in every instance of its use. Here it means to say “behold”. Again, the branch sign is a pictogram, and it simply means “branch”, while the middle sign, which looks like a lowercase “y” regardless of whatever it actually depicts, means “number”. The logogram at the right in this set is a mace, and it gives us the word, “one”. Here the Ugaritic word for “behold” (hn), is in a three way parasonance with the Ugaritic word for “branch”, (ht), and with the Ugaritic word for “number”, (hg). Here also, we see that the Ugaritic number “one” (`ahd), is involved in a three way pun with the Ugaritic words for “behold”, “branch” and “number”.

What this passage means to say — and in every whit poetically, at any rate, succeeds in so doing — is that this man, Our-Side-Branch-Great-Great, not a king but a progenitor of kings and a warlord, came forth out of the obscurity that most men spend their entire lives in, “manifestly” waging war; thereby “manifestly” founding as a consequence, “branch number one”. The attitude toward war was quite different in the Bronze Age. They were not only not ashamed of it, as many of us purport to be, but very much the opposite, quite overweeningly proud of it. At least they were honest in their sympathies. A1, A2, A3, A4 and A5 comprise a pentacolon in the form of an envelope parallelism. This parallelism has an ABCAD structure. In this parallelism, the adverb “manifestly” in the first A-line, exactly parallels the same adverb, “manifestly” in the second A-line; the B-line, “warring”, thematically parallels the C-line “Our-Side-Branch-Great-Great” because he is the one doing the warring. The C-line “Our-Side-Branch-Great-Great” is also thematically paralleled by the D-line “behold branch number one”, because he is the founder of said branch. And despite the fact that this closing D-line stands outside the envelope, it is nonetheless part and parcel of the same parallelism.

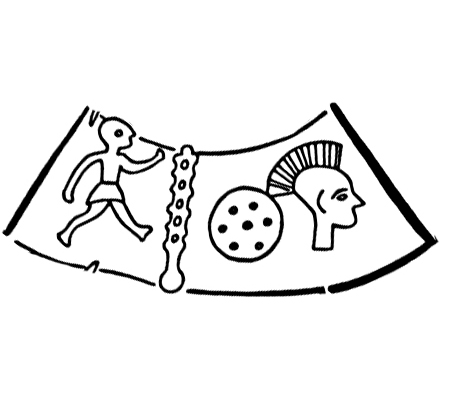

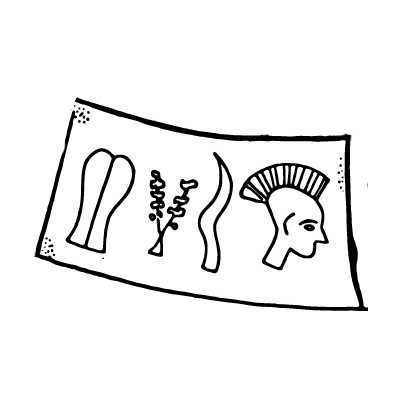

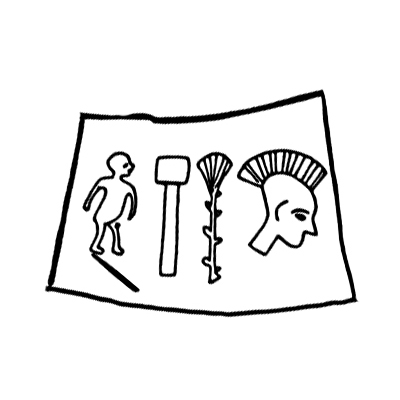

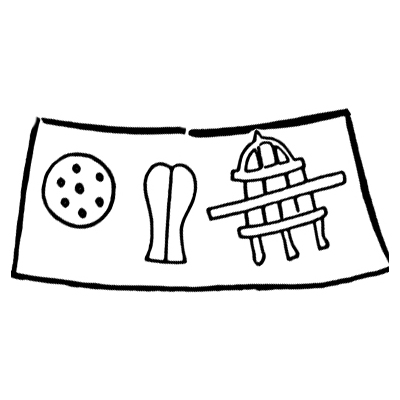

At A6 is a man’s name, “Warrior”. The walking man for the verb “walking”, begins this set. To the right of this, is the war club logogram for the verbs “strike” and “struck”. In this instance the verb is “strike”. And these two signs are combined as units within the endocentric compound, “walking strike”, i.e. the noun “war”; to be glossed, “Warrior”, since this is a man’s proper name. The Ugaritic verb “walk”, is spelled hlk. The Ugaritic verb “strike”, is spelled hlm. These two verbs then, are in parasonance. The shield sign for the word “important”, is next in this set, and it stands next to the mohawked man’s head sign for “man”, “men”, “maker”. In this instance, the word is “man”. This sign configuration means to tell us that this is the name of an important man. When the two signs for “important” and “man” are paired with proper names, epithets and titles, however, the words “important man” are silent. The Ugaritic word bns, means “man”, the Ugaritic word bnsm means “men”. These two words then, are involved in a pun with each other. The Ugaritic word for “maker”, is nsk. And so this word is in parasonance with the Ugaritic word for “man”, as above, bns.

At A7, are logograms consisting of the shield, the bull’s horn and a bird of prey, probably an eagle. Together these signs mean, “important king deified”. The shield logogram for the word “important” begins this set; the next sign to the right of this shield, is the bull’s horn logogram and it gives us the words “king” and “royal”. In this instance the word is “king”. To the right of these signs, is the eagle logogram. The eagle was, in some cultures in the ancient world, a psychopomp (a conductor of souls), which being was a standard concept in Ugaritic religious thought. This eagle carries something in its talons, it depicts a psychopomp carrying a deceased king to the netherworld. This sign gives us the word “deified” and alludes to Shapash, goddess of the sun, judge supreme and psychopomp to kings in the Ugaritic pantheon. A6 and A7 comprise a bicolon; a formal parallelism with an AB structure. Here, although there is no true parallelism (as per all formal parallelisms), the idea contained in the A-line, “Warrior”, is elaborated upon in the B-line, “important king deified”.

This man died without male issue, evidently, or perhaps without any issue at all, and A8 explains what happens next: “number three upon (a) woman”, this is to say, through a related female line. The logogram for the word “number” begins this set. To this logogram’s right, is the logogram for the number three, thus giving us the word “three”. The next sign in this set, is a sideways chevron; this logogram gives us the prepositions, “for”, “from”, “upon” and “with”. In this instance, the preposition is “upon”. To the right of this, is a pictogram for the word “woman”. This woman, whoever she was (certainly whichever of the deceased king’s wives had royal prerogative in matters of inheritance: the chief queen, or rabitu), was automatically of the royal line by virtue of being the widow of the deceased king, and when she remarried it was probably to a man of lesser rank; hence the phrase “upon woman”, rather than through some royal male identified by name. This unnamed man was probably a cousin of the deceased king, rather than a brother. This would explain why Our-Side-Branch-Great-Great is not listed as Warrior’s father, because he was not, he was probably Warrior’s uncle and after Warrior’s death, the queen mother married the son of Our-Side-Branch-Great-Great. This man is not named on the disk because he was not of the royal line. After all, the royal line – not the genealogy – starts with Warrior, not Our-Side-Branch-Great-Great. A type of levirate marriage, called yibbum, to her deceased husband’s cousin was allowed, and this would have enabled her to inherit her late husbands estate, provided he had no brothers who might lay claim to it. At Ugarit, royal descent through the female line was allowed when circumstances required it; matrilineal descent was mandatory for the ancient Elamite dynasties, this is the case with the Egyptian royal lines as well, and a tradition of matrilineal descent has been kept alive to the present day, by Jews.

The second sign on the left in A8 is somewhat odd. We do know that whatever this sign in A8 is a depiction of (a pot lid, or a shoemaker’s knife?), it is not the number “one” because we have already encountered it. We will encounter “two”, but this is not it. I have identified this logogram as the logogram for the number “three” on the following basis: If the item in question is a shoemaker’s knife, its blade was made of copper or bronze. The Ugaritic word for both copper and for bronze, is “talatu”. This is also the Ugaritic word for the number three. And If we have identified this sign and its meaning correctly, then this would mean that the word for woman, `att, is engaged in a pun with the word for three, tlt, linking mother to child by means of parasonance. As above, parasonance is a type of word play where the noun or verb roots of two or more words differ from each other in one of their three or more radicals.

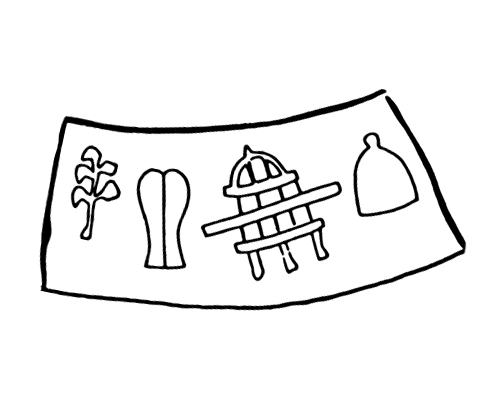

This “number three” is found at A9: “Oxhide”, a proper noun composed of no less than seven signs, employed for a specificity that such signs can only express by piling sign upon sign upon sign; in this instance, in order to differentiate “Oxhide” from any of this sign’s other meanings, since a total of five words share this same sign. It reads “oxhide from place oxen hides”, and by “place oxen hides”, it means a tannery. In this set, the oxhide sign to the far left (in this instance the meaning is “Oxhide”); the sideways chevron for the words “for”, “from”, “upon” and “with” (here the meaning is “from”); the dove sign for the word “place”; the oxbow yoke sign for the words “ox” and “oxen” (in this case the word is “oxen”) and the oxhide sign at the far right in this set (in this instance the meaning is “hides”) are all acting as the component parts of an endocentric compound. As above, the third sign from the left in this set is a dove and it is the logogram for the word “place”. This word place is engaged in a word play with its sign, the dove. The word for dove in Ugaritic is ynt, a noun. The word for “to place” in Ugaritic is, ytn a verb. This word play is called anagramic paronomasia. This occurs when the radicals of two or more roots are simply anagramic to each other, and both paronomasia and parasonance can work across parts of speech and violate other aspects of grammar, such as tense, etc. This pun, however, like some of the others in this text, would have been lost on a listening audience, since it is in essence a visual pun; scribes at Ugarit were fond of visual puns. A verbal pun like we saw with the words “three” and “woman”, would have been communicated through pronunciation rather than trough visual cues and certainly not through spelling, since no Ugaritic alphabet existed at this time in history. We will see this sign twice more.

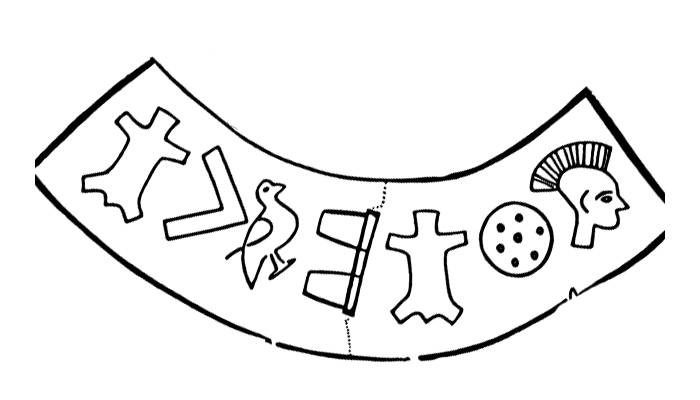

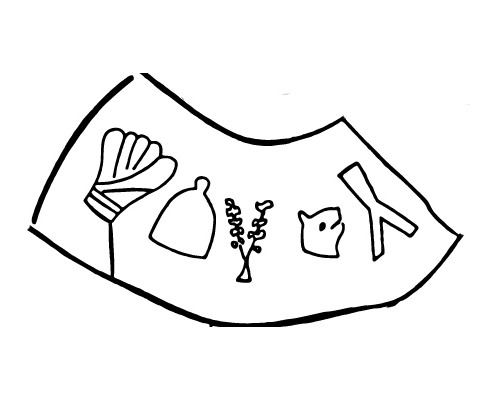

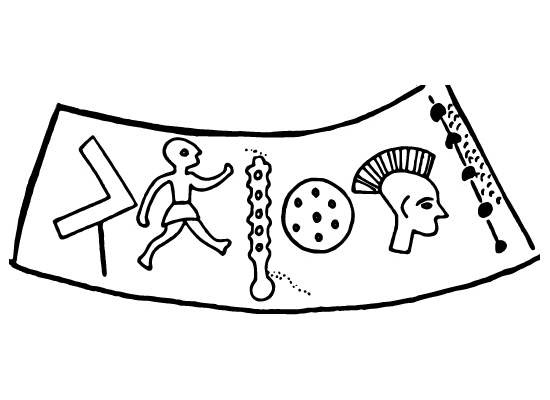

Counting from A1 round the disk, one can see that Oxhide is indeed the third important man listed, confirming the choice of “three” in A8. He is also the second king so called by name, for at A10, is the logogram for the words “king” and “royal”, the bull’s horn. In this instance, the word is “king”. Projecting downward from this sign, is an oblique slash; the logogram for the words, “he”, “it”, “they” and “behold”. In this case, the word is “behold”. To the right of this, is the bird of prey sign, logogram for the word “deified”. We have seen this sign once and we will see this sign again, but unlike all the other examples of this bird of prey sign on the disk, this one is flying upside-down. The artist meant for this sign to face upright. This sign got past the editors, and I class the unusual positioning of this sign an unimportant typographical error. The sign to the far right in A11, is a depiction of a foreleg of an ungulate. This is the logogram for the word “sired”, a verb and its meaning is altered by the walking man to its left, a determinative; so that the word becomes another verb, “fathered”. Projecting downward at the far left in this set is the diagonal slash, the logogram for the words “he”, “it”, “they” and “behold”. In this case, the word is “he”; giving us the two word phrase, “he fathered”. At A12 is a man’s name. The sideways chevron logogram for “for”, “from”, “upon” and “with”, begins this set. Here it gives us the word, “with”. To the right of this, is the mace logogram for the word “one”. To the right of this, is the oar pictogram for the word “oar”. To the right of this, is the ship pictogram for the words “ship”, “ships”, “boat”. Here it means to say, “boat”. To the right of this, is the oxhide sign for “hides”, “leather”, “oxhide”, “great” and “greatly”. In this instance, the word is “leather”. The sideways chevron logogram, the mace logogram, the oar pictogram, the ship pictogram and the oxhide sign are all acting as units within an endocentric compound, “Coracle”; literally, “with one oar boat (of) leather”. To the right of these signs, is the mohawked man’s head sign, for “man”, “men” and “maker”. In this instance, the word is “maker”, so that all these signs together give us yet another endocentric compound: “Coracle-Maker”. Notice that in this set, despite the fact that this is clearly a man’s name, there is no shield sign for the word “important”. Whenever the shield sign in anyone’s name is absent, this means that we have an occupational name, evidently derived from said person’s vocation. We will see more of these occupational names. A8, A9, A10, A11 and A12 constitute a tetracolon in the form of a chiasm. This parallelism has an ABCD structure. In this parallelism, the A line, “number three upon woman”, parallels the D-line “he fathered Coracle-Maker”, with a parental theme. The B-line, “Oxhide” thematically parallels the C-line, “behold king deified”, because Oxhide is the deified king at issue.

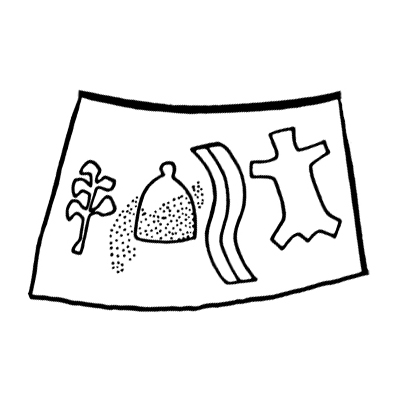

At A13 is the clause, “behold king deified”. But look at what happens in A14, not “he fathered” but the phrase, “one related”. The mace logogram for “one” and the fish sign, the logogram for the words “like” and “related” (in this instance, the word is “related”), are both acting as units within an endocentric compound. And please note the noun-adjective pairing of the phrase “one related”, that we look for in a proper Ugaritic word order. This “one related” at A14, who is in fact one and the same as the Coracle-Maker in A12, is the uncle or senior first cousin once removed, but not the father and probably not a brother (see below) of the next male in the line of succession (A15); and so the sense here, is that “one related” means to say “fostered”.

At A15 is to be found this kings epithet: “Our-Side-Branch-Great-Great”, a repeat of A3 and the noun-adjective sequence “side branch great great”; this is a doublet, a name doublet actually, of the first Our-Side-Branch-Great-Great. But observe that the ox hides in this name, face the ox hides in A3. These two, A3 and A15 are referencing each other and are great great grandfather and great great grandson to each other, respectively. If this is the case, then it precludes A14 and A15 (who we already know are not father and son) from being brothers. At A16 is the clause, “behold king deified”. At A17 are words made up of the walking man as determinative and the foreleg sign for “sired”; beneath this is the diagonal slash sign for “he”. As above, these signs combine to give us the verb phrase, “he fathered”. Then at A18, is the endocentric compound “Coracle-Maker” again, giving us another name doublet. Note that this Coracle-Maker is not titled “king” in the text. We are meant to suppose that he was killed, along with most of his family, in the sudden onset of the flood possibly as an adult, but while his father was still king. In regard to the next parallelism, there is an enjambment, because A11 and A12, which have already been discussed, are also being used here; so that A11, A12, A13, A14, A15, A16, A17 and A18 comprise a hexacolon with an ABACAB structure. In this parallelism, the first A-line, “behold king deified” parallels exactly the second and third A-line, “behold king deified”; the first B-line “he fathered Coracle-Maker” parallels thematically the C-line “fostered Our-Side-Branch-Great-Great” and exactly parallels the second B-line “he fathered Coracle-Maker”. This is an envelope parallelism.

That the names in so short a sampling repeat, is not so surprising when we consider that names do repeat, occasionally, in authentic pedigrees. After all, if you have an effectually infinite pool of Amorite — or whathaveyou — names for an archaic fictional genealogy, why bother repeating them? The answer is simple enough; namely, that there is a thread of validity running through this particular genealogy. The presence here of the anonymous queen mother of Oxhide, and the adoption of the second Our-Side-Branch-Great-Great, also lend weight to this argument; since a fictional genealogy from the Bronze Age, needs no such detail. So it is an authentic genealogy in part, but an ancient one, and that’s why its authors have had to substitute epithets for real names where faulty memory has made it necessary; the final count of antediluvian ancestors was then arranged to better accord with the mythologically freighted number, seven. This genealogy, however, can neither be called antediluvian, nor postdiluvian, since there never was a deluge — in the classical sense of that word — in the first place; this is simply a very ancient, half remembered genealogy, with a mythical flood narrative that has somehow managed to become attached to it.

A Word About Itinerary

The disk should properly be read in the correct order: recto, verso, recto. The disk was made this way in order to keep all the chaos and violence of flood and war on the verso side and the more stately and somber themes of deceased ancestors and flood memorial on the recto side, while still affording the reader a fully comprehensible narrative. The division between the sacred and the profane is a very old concept worldwide; for those cultures with origins in the ancient Near East, this is especially true, even up to the present day.

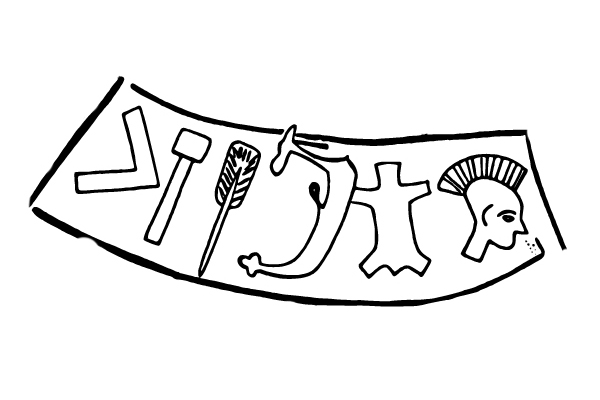

At A19 is found a logogram depicting what is clearly a recurved bow that Sir Arthur Evans defined as Asiatic Composite, that is to say, a Near Eastern composite type that had its origins in western Asia. And he was certainly correct. This military technology eventually found its way into the armies, navies and cavalries of city states and empires throughout the ancient world. There is simply no credible evidence, however, for Minoan use of this style of Asiatic composite bow. This bow resembles the Scythian bow, but the style is actually much older, and Scythians would not step onto the stage of history until the 8th century BCE. In Greece, this type of bow would first appear on Attic vases from the 6th century BCE, so any evidence for Mycenaean use of this type of bow before, or during the time of, the Mycenaean invasion of Crete, is non-extistant. Regardless, a Mycenaean culture — probably Achaeans — sacked Phaistos in the 15th century BCE (at which time the palace collapsed on top of the disk) and appear to have left the area soon thereafter, since there is no evidence for Mycenaean occupation of Phaistos after this. Any inclusion of this type of Asiatic bow on a Minoan or Mycenaean Phaistos Disk is, therefore, out of the question. The 3rd millennium BCE on the other hand, saw the debut of this type of composite bow in the ancient Near East, namely in the Akkadian Empire of the 23rd century BCE during the reign of one Naram-Sin. Amorite tribes had the misfortune of coming into violent contact with this very king at Jebel Bishri (Mountain of the Amorites) and were defeated by him there, and no doubt these tribes learned of the Asiatic composite bow at that time, or some time not long after. A gaping window of opportunity indeed, for inclusion of said bow on an Ugaritic Phaistos Disk. This bow is an allusion to the Ugaritic goddess of war, ‘Anat, who evinced a rather homicidal fondness for the bow. One of ‘Anat’s titles was Destroyer, and “destroyer” is exactly the word this bow sign means to convey. Kld is one of the Ugaritic words for “bow” (this is Hurrian, but definitely used by Ugaritic scribes in the 2nd millennium BCE); klh is Ugaritic for “destroy” — to be glossed “destroyer”. And so once again we have an example of a sign engaged in a pun, this one a parasonance, with its near meaning like we saw at A9. And again, this visual pun would have been lost on a listening audience. There is also a pictogram of a barleycorn in this set. Ba’al Hadad, ‘Anat’s brother, was a typical ancient Near Eastern dying/rising god and Ugaritic god of rain for barley and other crops, storms and other aspects, and by virtue of the barleycorn, this passage is a reference to him as well. The Ugaritic word for the type of barley given to animals, i.e. fodder, is `akl. We therefore have the words for bow, kld; destroy, klh and barley, `akl, involved in a three way parasonance. As well, there is a bit of allusive paronomasia here, since mdl, which is Ugaritic for “thunderbolt”, but which word does not actually appear in this text, is in parasonance with kld, ‘Anat’s bow, thereby evoking Ba’al’s thunderbolt. This is no accident. With the bow and barleycorn, and given this context, I would therefore assign this set the value: “destroyer (of) barleycorn”, i.e., “storm”, since storms of sufficient strength — particularly hailstorms — can be very detrimental to crops. These three signs are all acting as components in an endocentric compound.

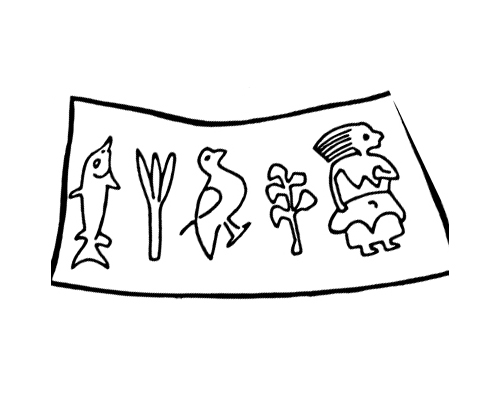

As for the question of deified kings, Amorite royalty buried their dead beneath threshing floors and other necropoli, and such places were considered portals of the dead ancestors, which ancestors for instance, would be those we’ve just been discussing: none other than the Rapi’uma (aka Rephaim), the dynastic guarantors and deified kings of Ugarit. From an Ugaritic alphabetic cuneiform text, ca.1200 BCE, KTU 1.20 II 5-7a: They journeyed a day and a second. After su[nrise on the third] the Saviors arrived at the threshing floors, the di[vinities at] the plantations. Even in that age, it seems, it took only three days to travel from the underworld to the world of the living. At this point we must flip the disk over to its verso side and start again in the center, at B1.

Scroll cells A01 through A19

Side B

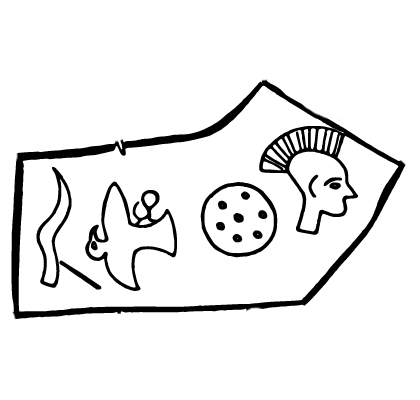

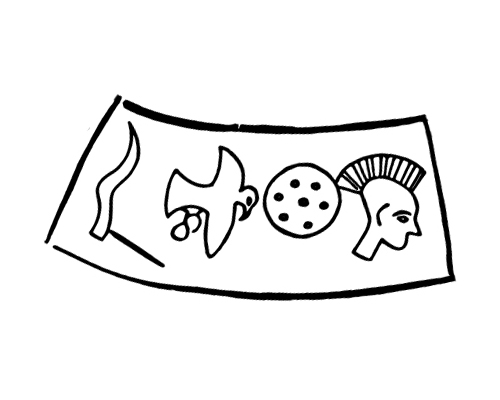

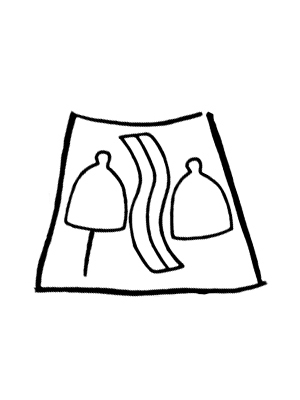

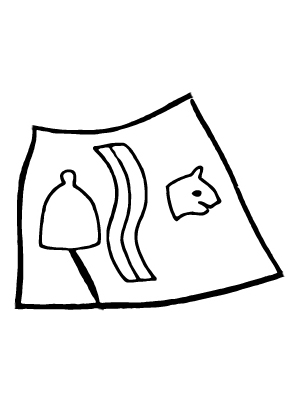

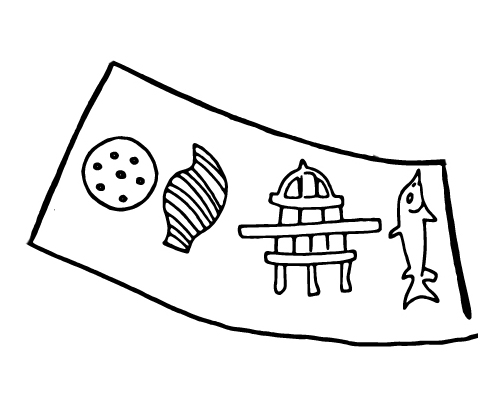

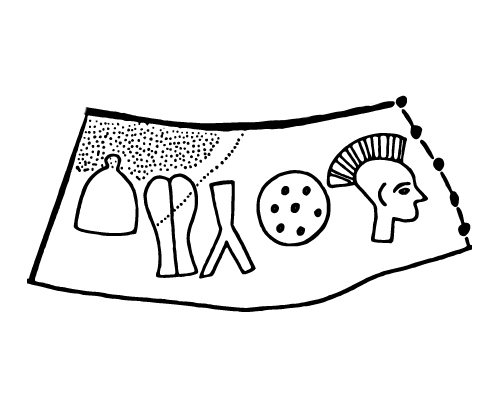

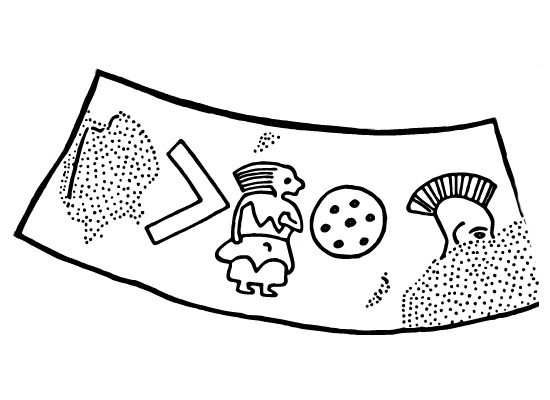

At A19 and B1 we find the clause, “storm it came flood”. The sign at the beginning of B1 is a logogram of a breast, surely an apt symbol of issuing forth; thus giving us the words “came”, “destroyed”, “fell” and “went”. In this instance, the word is “came”. Projecting downward from this sign, is the oblique slash sign, logogram for the words “he”, “it”, “they” and “behold”. In this instance, the word is “it”. The second sign in this set, a wave shaped stripe with a line down its middle, is the logogram for the word “flood”. The Ugaritic word for “storm”, is gsm; and as above, mgy is a serviceable Ugaritic verb for “came”. So these two words are in parasonance. A19 and B1 comprise a bicolon, another formal parallelism to be exact. This parallelism has an AB structure. In this parallelism, the idea of the A-line, “storm”, is extended into the B-line, “it came flood”.

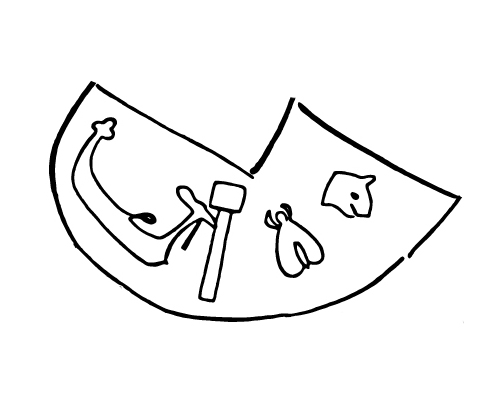

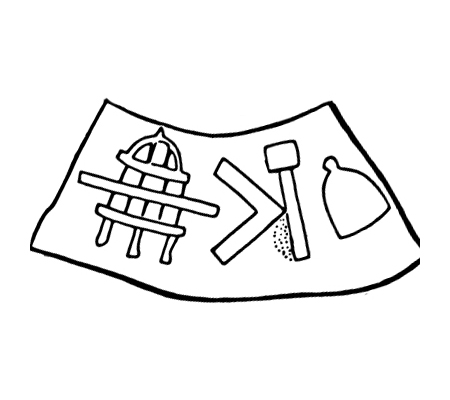

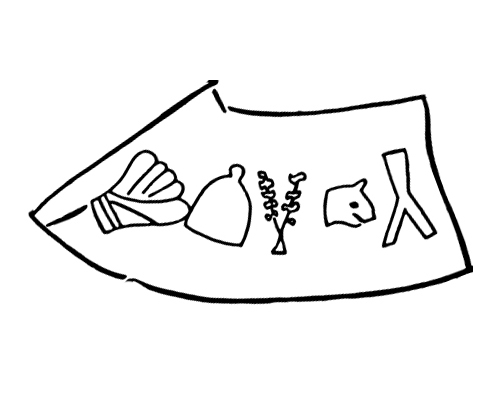

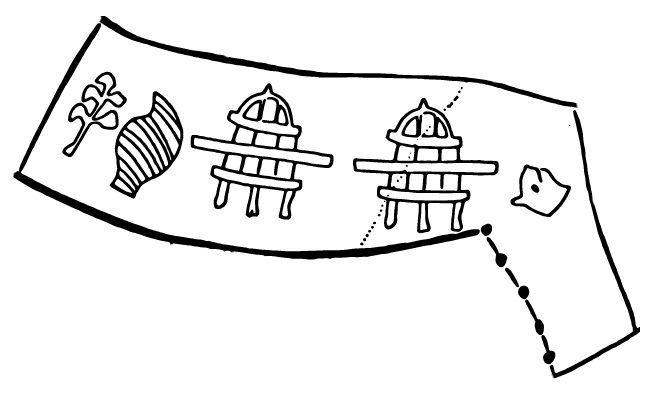

At B2 is the clause, “ship one loaded animals” or, one ship loaded the animals. The ship pictogram for “ship”, “ships” and “boat”, begins this set. And next we see again, the mace sign for “one”. The cardinal number 1 in Ugaritic is a noun, but in certain cases the word “one” acts as an adjective; as in this case, when it is synonymous with the adjective, single. We therefore have yet another example of the noun-adjective pairing logical to Ugaritic word order. The ship as illustrated here means “ship”, but with its acutely upturned bow and stern, it looks nothing like the long boat style ship so typical of Minoan seafaring, rather, it strongly resembles the sort of papyrus reed craft that was de rigueur all across the ancient Near East during the Early and Early Middle Bronze Age. At the time the disk was made, these folk might have constructed their ships of wood, or partly wood and papyrus reeds or leather, regardless of what type of ark this flood narrative originally envisioned in its early preliterate stage of development — a reed coracle perhaps (see I. Finkel, The Ark Before Noah: Decoding the Story of the Flood); but it seems clear to me that this ship’s design is at least modeled on an earlier reed type. I say ships, simply because that’s how this early 2nd millennium Ugaritic culture would have viewed the matter. Based on their size alone, we would call them boats. Anyway, if these ships were made of papyrus reeds then they weren’t made by Minoans, and Sir Arthur Evans correctly noted the non-Minoan style of these ships. It’s simply that the climate of Crete was not conducive to the support of the large and healthy stands of papyrus needed for that sort of ship building; although one supposes they could have imported Syrian papyrus (cyperus syriacus, native to Syria and Sicily from Sicily); and if this species of papyrus was inappropriate for all this, they — or ant Ugaritic boatwright for that matter — might have imported papyrus reeds from Egypt. But Minoan ships were made of wood and always had been, so there was no need to.

Notice the peculiar figure upon the bow (right end) of the ship sign, which resembles nothing so much as a large horizontal wooden spoon-like object attached to the bow, with the business end of our “spoon” facing left and a vertical piece projecting downward from the “handle” of said spoon-like object, which faces to the right. The Phoenician cousins of our Amorites had figureheads, called pataeci, upon their warships and that might be what is depicted here. The Greek historian Herodotus (ca. 484-425 BCE) wrote about these figures, saying that these pataeci were god images that the Phoenicians attached to the bows of their warships. These pataeci were anciently associated with the Greek god Hephaestus and the Egyptian god Ptah, which gods were both a type of Kothar-wa-Khasis; a character in this story we will meet up with, very soon.

In this set we see an unusual sign (third from left in B2) that some have insisted is a bee or some such flying insect; it is not. This sign is a logogram, and it actually depicts a pack-load, the sort of thing one would use to carry clothes, bedding, tools or other assorted items for short distances. This sign gives us the words “boarded” and “loaded”; in this instance, it is the word “loaded”. To the right of this pack-load sign, is a decapitated cat’s head; this is the logogram for the words “animal” and “animals”. In this instance, the word is “animals”. And it makes no difference whatsoever to this text, or its understanding, what direction any of the decapitated cat’s heads in this text happen to face.

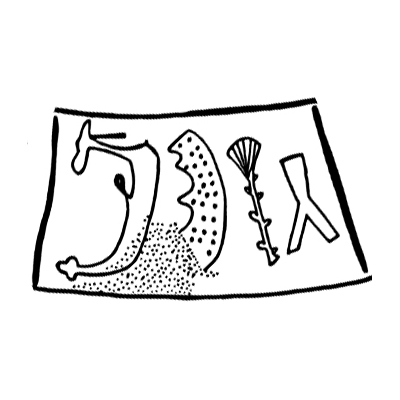

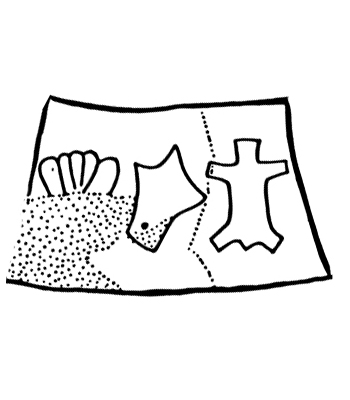

At B3 is the clause, “went one family”. Here is the breast sign for “came”, “destroyed”, “fell” and “went”. In this case the verb is “went”. Next, the mace sign gives us the word “one”. Here we see the branch pictogram for the word “branch”, the woman pictogram for the word “woman” and the mohawked man’s head sign for the word “man”, “men” and “maker”, all in a row. Here, the intended word is “man”. In this set, the branch sign, the woman sign and the mohawked man’s head sign are all acting as units within an endocentric compound, giving us the word “family”. At B4 is the phrase, “went with livestock clothing”. Here the breast sign for the verbs “came”, “destroyed”, “fell” and “went” begins this set. In this case, the verb is “went”. Next in this set, is the sideways chevron for the prepositions “for”, “from”, “upon” and “with”. In this instance, the word is “with”. We see here also the barleycorn pictogram and the ram’s head sign. As above, the barleycorn is a pictogram, and it simply means “barleycorn”. The ram’s head sign is a logogram, and it means “eater”; together, these two signs are uniting within an endocentric compound, giving us the words “barleycorn eater”, i.e. “livestock”. As above, the Ugaritic word for the sort of barley reserved for livestock, i.e. fodder, is `akl; this is also the Ugaritic spelling for the word, “eater”. This homonym as pun, is deliberate. The sign at the far right in this set has been identified as a tiara or an arrow head; it is nothing of the kind. This sign depicts an article of clothing, a cloak to be precise and gives us the word “clothing”.

At B5 is the sentence, “behold sea came over animal kind”. The first sign in this set is a depiction of a sea shell, probably a mediterranean conch: charonia tritonis. It is a logogram, and it gives us the word “sea”. Projecting downward from this sea shell sign, is the diagonal slash again and as above, this is the logogram for the words “he”, “it”, “they” and “behold”. In this instance, the word is “behold”. Next in this set, is the breast sign for “came”, “destroyed”, “fell” and “went”; here it gives us the verb, “came”. The third sign from the left in this set depicts a plant with long limbs and a rather stout base, resembling watercress. It is a logogram, and it gives us the words “high” and “over”. In this instance, the word is “over”. And within this sign, the word “high”, `il, is engaged in a parasonance with its partner, the word “over”, `al. To the right of the watercress sign, is the cat’s decapitated head again. And again, this is the logogram for the words “animal” and “animals”; in this instance, the word is “animal”. The last sign in this set looks something like an upside down, bold, uppercase “Y”, and it has been identified by some as a sling. I have no argument with that, although I wish I did since it doesn’t look very much like a sling. It has also been identified by some as a double pipe. I’m not entirely convinced of that either. No matter, it is a logogram, and it stands in for the words “kind”, “type” and “types”; in this instance, it is the word “kind”.

B2, B3, B4 and B5 comprise a tetracolon in the form of a chiasm. This chiasm has an ABB’A’ structure. In this parallelism, the verb “loaded” in the first A-line, parallels the verb “behold” in the final A-line; The word “one” in the first A-line, parallels the word “one” in the first B-line. The noun “ship” in the first A-line, thematically parallels the noun “sea” in the final A-line; the verb “went” in the first B-line exactly parallels the verb “went” in the second B-line, and the noun “animals” in the first A-line parallels the noun phrase “animal kind” in the final A-line. The sentence “went one family went with livestock clothing”, constitutes the sort of poetic structure called a pivot pattern, so essential to the chiasm in Ugaritic poetry. And finally, the noun “family” in the first B-line thematically parallels the noun “livestock” in the second B-line. The humor implicit here, is deliberate.

At B6 we find the phrase, “house upon one fell” or, fell upon one (i.e. a single) house. The house pictogram for the word “house” begins this set. To the right of this, is the sideways chevron logogram for the prepositions “for”, “from”, “upon” and “with”; here the word is “upon”. Next we see the mace logogram for the word “one”. To the right of this, is the breast logogram for the verbs “came”, “destroyed”, “fell” and “went”. In this case, the verb is “fell”. The noun-adjective sequence, “house” and “upon one”, is the Ugaritic word order we have already encountered. And by “house” the authors mean dynasty. The authors do not wish to imply that the flood fell upon one family only, however. Surely it was their understanding that this flood would have fallen upon all houses, but not upon all houses equally. Are the authors of the disk intimating that the flood protagonist’s house was singularly tasked with surviving the flood, that the responsibility of saving all humanity fell upon one house? In every other ancient Near Eastern flood narrative, this is the case; the protagonist is warned in advance. Perhaps in the oral retellings of this story, this was made more explicit. Is there a subtext here?

One example of this flood warning, comes from the `Atrahasis flood narrative. The gods are disturbed at all the noise that humankind is making, so Enlil, king of the gods, decides to destroy them. Enki, god of mischief, intelligence, creation, etc., takes pity of his servant `Atrahasis (exceedingly wise), so he decides to warn him. Having promised Enlil, however, that he will not reveal the plan to any mortal, Enki devises another way. He tells a wall of `Atrahasis’ reed house instead: Wall, listen constantly to me! Reed hut, make sure you attend to all my words! Dismantle the house, build a boat, reject possessions, and save living things he says, technically keeping his word to Enlil. In this way, Enki reveals all and, as intended, `Atrahasis overhears. At B7 is the clause, “it destroyed flood destroyed”. Here we see the breast logogram for the verbs “came”, “destroyed”, “fell” and “went”. In this case, the verb is “destroyed”. And projecting downward from this, the diagonal slash for the words “he”, “it”, “they” and “behold”. In this case, the word is “it”. To the right of this, is the wavy stripe logogram for the word “flood” and then the breast sign again, for the words “came”, “destroyed”, “fell” and “went”. Here the word is “destroyed”. At B8 is the clause, “branch upon fell” or, fell upon (the) branch. By now we should know that the branch pictogram to the left in this set, is giving us the word “branch”. Here the sideways chevron logogram for the prepositions “for”, “from”, “upon” and “with” is, in this instance, giving us the word “upon”. To the far right in this set, the breast logogram for the verbs “came”, “destroyed”, “fell” and “went”, is now giving us the verb “fell”. If the passage covering B6, B7, and B8 is somewhat difficult, here is a paraphrase: Fell upon a single house, it destroyed, flood destroyed, fell upon the branch.

B6, B7 and B8 comprise another parallelism, it is a tetracolon in the form of a chiasm. This parallelism has an ABB’A’ structure. In this parallelism the noun “house” in the first A-line, thematically parallels the noun “branch” in the final A-line, and the words “upon one fell” in the first A-line parallel the words “upon fell” in the final A-line. Here also we see that the pronoun “it” in the first B-line thematically parallels the noun “flood” in the second B-line, and the verb “destroyed” in the first B-line parallels exactly, the verb “destroyed” in the second B-line. And once again, with the clause “it destroyed flood destroyed” we have an example of the crucial pivot pattern for the chiasm. Now, these parallelisms we keep crossing paths with are a very old form of poetical structure, the sort one finds all throughout the Hebrew Bible; as above, however, the authors of the disk were not Hebrews and parallelisms can be found in Sumerian, Egyptian, Akkadian, Assyrian and Babylonian poetry as well. We will encounter more of these parallelisms.